[ad_1]

This section of the paper presents the key results of the study. The initial subsections of the analysis focus on the high degree of industrialisation within China’s cybercrime sector, paralleling, if not exceeding, developments in other countries. This industrialisation is evidenced by a highly differentiated market and the advent of cybercriminal firms. The subsequent subsection discusses the recent expansion of the Chinese cybercrime industry and argues that the Chinese cybercrime industry remains largely a local manifestation of the global cybercrime industry. The final subsection explores the ramifications of industrialisation, noting that jobs have become more simplistic, repetitive, and at times, monotonous.

The prevalence of cyber fraud and the rise the criminal market

While a multitude of cybercriminal activities prevail in China, it is undeniable that cyber fraud constitutes the core of Chinese cybercrime. According to a report provided by the China Judicial Big Data Research Institute, 282,000 cybercrime cases were adjudicated in the first instance by courts in China between 2017 and 2021. Of these cybercrime cases, almost 40% of the cybercrime cases were sentenced under the charge of cyber fraud. At the same time, 23.76% of the cybercrime cases were under the charge of assisting cybercrime, indicating the existence of a large group of cybercrime facilitators (The China Judicial Big Data Research Institute, 2022). The empirical evidence corroborates the findings presented in this judicial report, demonstrating the existence of a vast cybercrime market in China, centred on cyber fraud. Similar to most cybercrime operations, the data reveals that the effective execution of cyber fraud is contingent upon the collaborative efforts of diverse facilitators (Hutchings, 2018; Levchenko et al., 2011).

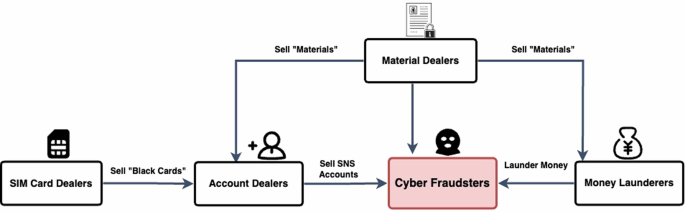

The empirical evidence delineates four pivotal groups of facilitators within the cybercrime market, as depicted in Fig. 1 below. The first group of facilitators are the SIM card dealers. Under the real-name registration system in China, citizen ID must be presented at the counter of the business hall when purchasing SIM cards (Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China, 2016, s.24; Provisions on the Registration of True Identity Information of Telephone Subscribers, 2013, s.3; s.5; s.6). The rationale behind this regulation is to ensure every phone call is traceable and locatable to an individual by the police for public management and criminal investigation reasons. However, in reality, there were countless phone numbers in the police tracking system with incorrect information or with no information at all. The numbers are called ‘black cards’ by the police (GZ-P-10, GD-P-20). These SIM cards were collected by the SIM card dealers and sold in bulk to the second group of facilitators: the account dealers for further illegal operations.

Account dealers are the second group of facilitators. Under the same real-name registration system, all online accounts must be bound to citizen ID. This is done via SMS verification. By linking the online SNS accounts to offline phone numbers, which are supposedly connected to citizen ID cards, the real-name system seeks to take public control over the virtual space as well as the offline dimension (GD-P-20, GZ-P-9, GD-P-19). However, the account dealers circumvent China’s strict real-name system by registering large numbers of social media accounts using the SIM cards purchased from the SIM card dealers and building genuine images for these accounts (known as ‘account farming’) to avoid detection by social media platforms’ security systems (GD-CSP-2, GZ-P-9, GX-P-1).

The third group of facilitators are material dealers. Material dealers are criminals who collect a variety of ‘materials’ that could be used to conduct cybercrime, including citizen IDs, bank accounts, bank cards with security devices, business licences, and other personal data (SX-H-1, SX-H-5, GZ-P-8, GZ-P-11, GD-PST-4). There are three main customers of the material dealers, all of whom need different materials: account dealers, cyber fraudsters, and money launderers (GD-P-2). For account dealers, filling in bank information for SNS accounts with citizen IDs and corresponding bank accounts can increase the creditability of the accounts and avoid detection more effectively, thus subsequently increasing the value of the SNS accounts (SX-H-5); for cyber fraudsters, acquiring personal data such as victims’ names, IDs and bank details enable them to conduct scams more effectively, and this acquisition is also essential for certain types of scam (GD-CSP-3, SX-H-5); for money launderers, entities such as bank cards, USB security keys and business licences are all necessary tools for money laundering (GZ-P-8).

The final group of facilitators consists of money launderers, who have been prominently featured in numerous cybercrime studies. In a multitude of cybercrime operations, there are typically individuals known as money mules engaged to aid the cash-out process for cybercriminals (Hutchings, 2018; Leukfeldt, 2014; Lusthaus and Varese, 2021). However, the situation in China reveals that these individuals are often not merely ‘money mules’ at the behest of cybercriminals, but professional business entities holding a critical role in the market, which is commonly referred to as a ‘water house’ by law enforcement (GD-CSP-3, GD-P-20, GX-P-1, GX-P-3, GD-P-22, GZ-P-8, GZ-P-10). A typical process within cybercrime money laundering involves acquiring bank cards from material dealers to dismantle the funds. For instance, a hundred dollars might be split into nine transactions of ten dollars each, distributed across ten different bank accounts, with the residual ten dollars further divided into ten one-dollar transactions, and then channelled into another set of ten separate accounts. After repeating the process three to five times and mixing the money transfers with numerous daily expenses in each layer, the money originally paid from the victim becomes difficult to trace (GZ-P-8). What’s more, on top of the money dissembling, money launderers may add fake digital currency or virtual property transactions at certain stages to conceal it even further (GD-P-22, LECID-5).

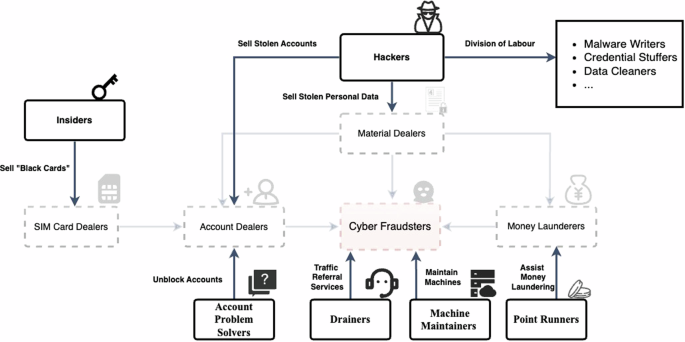

The aforementioned four groups of facilitators, however, represent merely a small segment of the market’s participants. The cybercrime market is considerably more intricate and divided, as shown in Fig. 2. On the one hand, criminal activities are often delegated to individuals performing more granular tasks for the above-mentioned facilitators. For instance, SIM card leaks may originate from insiders within mobile telecommunications companies: it is conceivable that during the registration of phone numbers, a teller might clandestinely register an additional SIM card using the customer’s identification details for subsequent illicit sale (GZ-P-10, GD-P-20). Likewise, hackers frequently supply account dealers and material dealers with stolen accounts and personal data. The value of these compromised accounts extends beyond the time savings afforded by bypassing the need for account farming; they also provide a crucial instrument for perpetrating scams that include the impersonation of a victim’s contacts (SX-H-1). Furthermore, there is a division of labour among hackers, such as those who are responsible for creating malware and those who are responsible for cleansing stolen data (US-CSP-2).

On the other hand, as the country’s efforts to prevent crime grow, so does the number of people helping with cybercrimes. For example, when it became clear that many online accounts were set up for fraud, social media companies started using new technology to spot and block these fake accounts, which led to many accounts being closed. In response to this, ‘account problem solvers’ have emerged as novel commercial ventures, offering services to liaise with SNS platforms and manage the account reinstatement process through online channels (GZ-P-9). Similarly, numerous cyber fraudsters have recently begun to exploit telecommunications equipment equipped with Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) protocols, enabling them to make phone calls remotely via a computer to reduce the risk of detection (GZ-P-4, GZ-P-9). They may also hire machine maintainers to swap out the SIM cards in the machines, service the machines, and frequently relocate them to evade police detection, thereby further enhancing their safety (GZ-P-9, GZ-P-10).

Another recently emerged facilitator is known as a ‘drainer’. These individuals offer traffic-referral services to cyber fraudsters. Their operation entails drawing in potential victims and enticing them to connect with the social media profiles controlled by cyber fraudsters (GD-PST-2, GX-P-2, GZ-P-6). Strategies adopted by the drainers are numerous. Common methods include publishing articles or news about investments with QR codes that connect to the cyber fraudsters’ SNS accounts or conducting streaming to attract an audience and later inviting them to add the streamer’s SNS account, which is in fact controlled by cyber fraudsters (GX-P-2, GZ-P-6). Finally, to increase the level of concealment and the efficiency of the money laundering process, some money launderers develop ‘point-running platforms’. In essence, these allow users (‘point runners’) to upload their bank account numbers and the QR codes of their mobile-payment platforms, such as Alipay. The money-laundering firms then provide these bank account numbers and QR codes to cyber fraudsters to receive the money transferred from the victims and use them as a part of the money-laundering process. The point runners earn a commission based on the amount involved in each transaction. They are required to pay a deposit equal to the money they will receive before the transaction (CSCR-3; GD-P-20, GD-P-22).

Yet even the actors introduced above are not exhaustive; many more cybercriminals are working in each business sector to support the functioning of the cybercrime market. The cybercrime market is also dynamic: what can be observed now is already very different from how it looked in the recent past, and its features will surely change again in the future (HEB-P-1, GD-CSP-1, GD-PST-2, US-CSP-2).

In sum, presented in this subsection is a highly specialised, dynamic cybercrime market that evolves continually under the influence of national policies in China. This finding aligns with previous research on international cybercrime, which suggests that modern cybercrime activities are rarely executed by solitary actors but rather through the collaborative efforts of various market participants (Hutchings, 2018; Lusthaus, 2018; Leukfeldt et al., 2017a; Soudijn and Zegers, 2012). Moreover, insufficient regulation in the areas of personal data protection, telecommunications, and mobile payment sectors, as the above empirical evidence presents, has contributed to the development of cybercriminal market in China. The easy access to products such as personal data, SIM cards, and telecommunications equipment, along with the widespread use of mobile payment services without a comprehensive regulatory system, leads cybercriminals to recognise the potential profits of focusing on specific tasks that facilitate cyber fraud. At the same time, crackdowns on these facilitating activities, without sufficient effort to improve regulations in these sectors, appear to be counterproductive and have contributed to the further development of the market. The rise of the market provides the soil for industrialisation.

The present of cybercriminal firms

Beyond the market, the empirical evidence also found a diversity of cybercriminal firms in China. These firms, engaged in hacking, cyber fraud, draining, and money laundering, have been identified within the broader spectrum of cybercriminal operations.

Haoming, a former hacker and a current cybersecurity engineer, explained how a cybercriminal group specialising in infecting servers and computers is commonly structured: “An infection team generally consists of three to five members. When there is a task given by the ‘exit’ [the leader who reaches out for business opportunities], the team members work together to accomplish it” (SX-H-1). Although there are often several stages to an infection process and the members have different specialities, the members’ roles sometimes overlap when working on a task, and the leader is often involved. The structure of such hacking groups seems to resemble most small-scale cybercriminal groups with a significant degree of online component, such as the Gozi group (Lusthaus et al., 2022) and some high-tech cybercriminal groups in the Netherlands (Leukfeldt et al., 2017a). Although these groups have relatively flat hierarchical structures and lack clearly defined roles among their members, the distinction between leaders and employees remains evident. As Lusthaus et al. (2022) put it, they are ‘situated on the defining boundary,’ which, overall, aligns with the concept of criminal firms. There are good reasons for firms like this to rise among the high-tech cybercriminals. The most significant factor is that cybercriminals conduct business in an unstable environment, facing constant threats from law enforcement and the risk of defection by their collaborators (SX-H-1). It is, therefore, preferable for them to form stable partnerships and internalise market transactions to avoid the trouble of identifying reliable partners for each venture. Haoming wrote: “If I want to do something, or I want to get something, I often need people, and I surely want to find someone I know, right? I can’t just go onto the internet and say: ‘Hi, who wants to hack with me?’” (SX-H-1). Moreover, time and efficiency are crucial in many situations. For instance, in the sale of vulnerabilities and data, early sellers typically command higher prices. Consequently, forming a stable team can minimise communication delays and other transaction costs, thereby enhancing efficiency and enabling members to achieve greater profits (SX-H-1, US-CSP-1).

Cybercriminal firms that employ a more hierarchical structure and align more closely with the theory of firms in legitimate world were also found. For example, Yueyi, the head of an anti-fraud centre at a county-level police station, described a cyber fraud group he had dealt with:

In 2018, we uncovered a group of cyber fraudsters who operated in the form of a company in Fujian Province. Inside the company, there was a promotion department, an IT department, and a sales department. The promotion department pretended to be attractive sales representatives, adding clients to WeChat and befriending them. Each of the company members controlled over 25 phones. These people would not take any money from you as this was the company’s regulation. They wouldn’t even accept your ‘pocket money’ [Hongbao] during festivals, so you would think you were talking to an honest person. Eventually, she would reveal this was her business WeChat account and invite you to add her personal account. By doing this, you were handed over to the sales department. People who worked in the sales department were the ‘real fraudsters’. They would tell you something like: ‘My grandfather is selling tea leaves, and I am helping him. The tea we sell is all naturally grown’, etc. In the end, they would sell you tea leaves for 800 yuan [approximately $125], and there was a product department that would really send you the tea leaves, but they were worth only 20 yuan [approximately $30]. Lastly, the IT department was responsible for handling the WeChat accounts. Sometimes their accounts were blocked by Tencent [the company that runs WeChat] for their suspicious behaviour, and the IT department tried to resolve the problem. They also maintained the electronic equipment used in cyber fraud, such as phones and computers. (GD-P-3)

Yueyi’s statement clearly demonstrates the group’s three-tiered hierarchical structure. Below the leader, there are various departments responsible for different duties. Beneath these departments are the employees who carry out the tasks. The distinctions among entrepreneurs, managers, and employees are pronounced.

As illustrated by the example above, this type of cybercriminal firm typically internalises many components of the market, such as machine purchasing and maintenance, traffic referring, and account problem solving. This approach not only enhances production efficiency, reduces communication costs, and mitigates transaction risks, but also effectively manages market price fluctuations caused by police repression (Coase, 1937). For example, a series of police crackdowns on the unauthorised sale of telecommunication equipment such as SIMBOX and GOIP in 2020 led to a dramatic increase in their price on the criminal market. It subsequently caused the price of related services, such as machine maintenance and SIM card transferring, to skyrocket (GZ-P-4, GZ-P-10).

Franchise-like operations have also been observed within some firms as part of their expansion strategy (GD-R-1, GX-P-1, GZ-P-6, GD-P-10, GD-CSP-2, GD-CSP-3, LECID-1, LECID-2). A confidential investigation report provides an example of how a cyber fraud group that conducted the notorious pig-butchering scam used this strategy to expand their business (LECID-2). A team leader of the group testified in the report:

Anyone who was able to recruit 10 members to form a group [team] could apply to become a group [team] leader, and the members he recruited would automatically join his group [team]. The group [team] leader had to cover half of the daily cost of the group [team] members, the cost of the office space and the office supplies, and the other half was paid by the boss. At the same time, the money earned by the group [team] was split equally between the boss and the group [team] leader. However, the group [team] leader also had to pay for the basic salary of the group [team] members. (LECID-2)

The testimony clearly demonstrates that cybercriminal firms not only mirror legitimate firms in their structure but also engage in similar economic activities as those conducted by businesses in the legitimate world.

In addition, it is worth noting that all cybercriminal firms found in this study had an offline component. Some degree of offline element appears necessary for coordination. Haoming, a former hacker, doubted that some firms operate ‘purely online’ and consist of anonymous members who only meet each other in that dimension. He noted that misunderstandings, disagreements, and arguments are almost inevitable in any group, especially for groups on a large scale or groups that perform complicated tasks. These issues will be amplified online as members cannot talk in person, and therefore the problems cannot be solved efficiently (SX-H-1). Furthermore, offline interaction seems to be inevitable to satisfy criminals’ social needs. Feiyue, another former hacker, held that the public impression about cybercriminals only communicating online, especially hackers, is mostly inaccurate. He said: ‘Hackers are humans. They have social needs. But hackers can’t only hang out with ordinary people, as they don’t understand each other. For example, if I tell you that I just made a shell, you will ask me what a shell is’ (SX-H-2). Therefore, members of a cybercriminal group, despite starting with anonymous online cooperation, will gradually come closer and start to develop offline connections.

This section demonstrates the existence of various cybercriminal firms in China. Although their structures may differ, they are formed to minimise transaction costs in the open market, consistent with economic theories (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1996). Beyond their structure, these cybercriminal firms also operate in ways similar to legitimate businesses. Furthermore, the incorporation of an offline element within these firms seems to have blurred the lines between them and conventional criminal firms as established in earlier research (Reuter, 1983; Von Lampe, 2015). Overall, the prevalent existence of cybercriminal firms in China indicates that Chinese cybercrime operates at a highly industrialised level, comparable to that observed in international contexts.

The global expansion of the industry

In line with newspaper coverage and previous studies, the empirical evidence also found traces of Chinese cybercriminals operating aboard, especially in East and Southeast Asian countries (Franceschini et al., 2023; Nguyen and Luong, 2021; Zhuang and Ma, 2021). For instance, some market actors of the Chinese cybercrime industry seemly operate in foreign countries. A police officer from Guangdong Province, Youpu, arrested some Chinese hackers from Cambodia in 2020. According to him, these hackers not only conducted hacking themselves but also sometimes subcontracted specific technical tasks to domestic hackers and distributed commissions based on the specific tasks (GD-P-19). Similarly, money launderers have also moved their operation to foreign countries such as the Philippines, Australia, and Middle East countries (GZ-P-8, SC-R-1).

Moreover, many cyber fraud firms have established themselves in foreign lands such as Myanmar. According to the participants, in areas such as Kokang, Shan State, Kachin, and Mengla, the cybercrime business is so flourishing that the criminals almost openly operate on a large scale in the fanciest building in town (GZ-P-6, GD-CSP-2, SX-H-4). Xinxue, a police officer, stated:

I went to Dehong once. It is a Chinese town bordering Myanmar. There is a river about five metres wide, and the cybercriminals are just over the river… We found some local guys to bring us over the border to Myanmar. When we got there, they introduced the subject of the buildings we saw from the other side of the river. These guys were all aware that it was a den of cybercriminals. We landed in front of a casino called Xinhe casino, which was the most famous casino in the town. The casino was like this: the first two floors were a casino, then there were seven floors; from the third floor up, each floor was a den of cyber fraudsters. (GZ-P-6)

Yet, while the firms are established in foreign countries, many of their members are recruited from mainland China and were smuggled to Myanmar. In a confidential investigation report, a recruiter of a cyber fraud firm located in Myanmar testified: ‘When a newbie is recruited [from China], the treasurer will cover the fees for flights and smuggling. He then must work for us for at least 3 months to cover these fees’ (LECID-1).

The empirical evidence seems to suggest that the Chinese cybercrime industry has reached a scale that extends beyond local manufacturing. In this regard, the development of the Chinese cybercrime industry appears to surpass cybercrime industries found in other countries, which are mostly domestically established (Lusthaus, 2018). However, the evidence also reveals that the participants in the Chinese cybercrime industry are almost exclusively Chinese, with limited involvement from foreign criminals. Additionally, there is not enough evidence to suggest that the Chinese cybercrime industry intersects or integrates with cybercrime industries in other countries. Therefore, the Chinese cybercrime industry remains largely a local manifestation of the global cybercrime industry.

Cybercriminals in the age of industrialisation

While the preceding subsections have focused on assessing the extent of industrialisation present, this subsection delves deeper to explore the influence of the industrialisation process on the routine operations of cybercriminals.

The first observable outcome of the industrialisation process is the development of an extensive value chain. This is characterised by a multitude of market actors, each specialising in distinct tasks, many of which require a relatively low level of technical expertise (GD-CSP-2, GD-CSP-3, SX-H-4, SX-H-5, SX-CSP-2, US-CSP-1, US-CSP-2). For instance, Fengshu, a police officer, described the daily tasks conducted by the account dealers:

These people[account dealers]’s task is to register and purchase social media accounts to resell them. They steal pictures and use Photoshop to edit them, creating personas that appear wealthy and attractive. To make these profiles look real, they also update the accounts with new posts every few days, building a genuine image. (GX-P-1)

The daily tasks of account dealers are repetitive and straightforward, with the ‘technical’ aspect of their work perhaps being limited to the image editing process in Photoshop. Similarly, regarding the tasks of material dealers, another police officer, Zhimei, posits that although some may possess hacking skills and access databases to steal personal data, most data is obtained through offline means:

A lot of personal data is sold offline. You put down your information at the [company] reception, and they may sell it at the back door right after you leave. I have seen some personal data sold as an Excel spreadsheet, printed, and on the top of the sheets, the companies’ names were still on it. (GD-P-10)

Reflecting on the same point, cybersecurity practitioner Chengzi claimed that ‘social resources’ are more important than technical skills for cybercriminals nowadays. He explained:

As long as you understand the theory [how cybercrime works] and possess your own ‘social resources’, there’s no need for technical skills to enter this field. For instance, if you are a telephone operator or know how to find one, you can start a SIM card business. We call this a ‘professional entry point’. (SX-CSP-2)

Even in business sectors where technical skills are essential, the level of expertise required is considerably reduced due to the process of industrialisation. For instance, in the context of hacking for data theft, cybersecurity engineer Ming observed that criminals need to acquire only a very specific set of skills to engage in this business, as they are responsible for just a small part of the overall process. Ming wrote:

Even in hacking, there’s a division of labour. Some are solely tasked with identifying vulnerabilities, while others exploit these weaknesses to steal data or user accounts. Then, there are those who compile this data, cleanse it, and structure it. All these activities are carried out as services, and the end products are sold to others. (US-CSP-2)

Addressing the same point, Youlv, a former hacker, even believes that anyone who acquires basic knowledge of computing or cybersecurity is capable of becoming a hacker (SX-H-5).

This characteristic of cybercrime tasks is even more pronounced for criminals who are employees of criminal firms, as there is typically an additional division of labour within these firms. As observed by Fengshu and Mandong, two police officers, members within many cybercriminal firms often operate as ‘ordinary employees’ (GX-P-1, GZ-P-9). Rules that resemble the company regulations of legitimate firms found in a case report can best support their claim. A group leader of a cyber fraud firm testified in the case report:

Our group members worked between 12:30–17:30 and 18:30–23:30. I checked the attendance every day, recorded who was absent, and oversaw their daily workload. On weekdays the members were not allowed to gamble in the casinos; they would face a 2000-yuan (approximately $310) fine each time they got caught. (LECID-2)

Another member from the same firm wrote: ‘There was a written regulation which stated that we had to add at least five friends on social media. If we didn’t hit the target, we had to work overtime for an hour and a half’ (LECID-2).

From the accounts given by these cybercriminals, it is striking to observe that typical corporate concepts such as office hours, performance indicators, work discipline, and overtime prevalent in legitimate businesses are equally applicable to the cybercrime industry. This finding strongly supports Collier et al.’s (2021) argument that as cybercrime becomes industrialised, this illicit economy begins to replicate the division of labour, cultural tensions, and alienation found in the mainstream economy, rendering the activities of cybercriminals into a profound and tangible experience of intense boredom.

Building on the aforementioned discovery, the second consequence of industrialisation on the activities of cybercriminals is that it obscures the boundary between cybercrime and traditional crime. As observed in numerous operations, whether by independent criminals or the ‘employees’, their tasks bear a close resemblance to those traditionally associated with street crime, such as the illicit trade of bank accounts and identity cards. Furthermore, there appears to be a minimal barrier for traditional criminals transitioning into cybercrime. This could account for the close associations between street criminals and cybercriminals observed in the Netherlands (Leukfeldt, 2014; Leukfeldt et al., 2019; Leukfeldt et al., 2017a; Leukfeldt et al., 2017b; Leukfeldt and Roks, 2021; Leukfeldt and Yar, 2016).

In addition, as has seldom been discussed in previous studies, as a result of cybercrime industrialisation, many tasks performed by cybercriminals, when viewed in isolation, may not be even readily classified as illicit. For example, the tasks of machine maintainers consist merely of swapping out SIM cards, maintaining the machines, and regularly relocating them. Likewise, the role of drainers is simply to encourage individuals to add certain SNS accounts to their friend lists. The activities in themselves do not constitute anything illegal. This has significantly increased the difficulties for law enforcement in tackling these cybercrime facilitators, as Yi, a police officer, complained: ‘If you consider these behaviours in isolation, they cannot be even deemed criminal. It’s only when you link everything together that you can categorise them as cybercrime’ (GD-P-8).

[ad_2]

Source link

Click Here For The Original Source.