[ad_1]

Key Points

-

The ransomware operator “Black Basta” has experienced a sharp decline following the public leak of its internal chat logs, but its legacy lives on.

-

Despite the group’s dissolution, former members continue to use its tried-and-tested tactics, with mass email spam followed by Teams phishing remaining a persistent and effective attack method.

-

Recently, attackers have introduced Python script execution alongside these techniques, using cURL requests to fetch and deploy malicious payloads.

-

To counter these threats, organizations should prioritize user education on phishing tactics. Informed and vigilant employees are often the first and most effective line of defense, stopping social engineering attacks before they succeed.

In February 2025, the infamous Russian-speaking ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) group “Black Basta” collapsed after a dramatic internal fallout. A disgruntled member, known as ExploitWhispers, leaked the group’s private chat logs on Telegram, frustrated by its controversial decision to target Russian financial institutions.

This leak not only revealed the inner workings of a high-profile ransomware operation but also led to Black Basta’s apparent disbandment. Once responsible for naming up to 50 victims a month on its data-leak site, the group went silent after February, and by the end of the month, its data-leak site had vanished entirely—marking the end of operations under the Black Basta name.

Now, just three months later, new ransomware groups like “3AM” are taking pages from Black Basta’s playbook, particularly its signature phishing tactics. Far from being a relic of a defunct group, the leaked chat logs offer invaluable insights into defending against today’s evolving threats.

With Black Basta’s history of targeting a broad range of industries across the US and Europe, the lessons from the group’s downfall remain highly relevant—helping organizations anticipate and counter the next wave of attacks before they strike.

In this report, we delve into Black Basta’s operations and its lasting influence on the ransomware landscape, drawing insights from its leaked chat logs to reveal:

-

The inner workings of Black Basta, including its tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), and how these tactics are likely to evolve.

-

Key dynamics within the group, its members, and affiliates—and where they may have resurfaced.

-

Practical steps organizations can take to defend against the tactics used by Black Basta affiliates and other ransomware groups employing similar methods.

Inside Black Basta’s Leaked Chats

How Black Basta Adapted to Stronger Defenses

The leaked private chats reveal how Black Basta deployed a wide range of tools and tactics across multiple phases of the kill chain. The group’s ability to adapt quickly allowed it to exploit weaknesses in an organization’s defenses, seamlessly shifting strategies when faced with strong countermeasures. This highlights the need for robust and comprehensive defense measures that address a broad spectrum of threats rather than focusing narrowly on specific tactics.

For instance, overly prioritizing protections against one tactic—such as brute-forcing—can unintentionally leave gaps elsewhere, like phishing via Microsoft Teams. To address this, ReliaQuest offers an extensive detection library designed to deliver holistic coverage across multiple layers of security, helping organizations stay prepared for a wide range of attack methods. The table below outlines some of the TTPs used by Black Basta across various stages of the kill chain:

|

Tactic |

Techniques and Tools |

|---|---|

|

Reconnaissance |

Gathered victim revenue data using ZoomInfo business intelligence. |

|

Reconnaissance |

Identified exposed services and ports through Shodan. |

|

Reconnaissance |

Collected exposed company and employee details from Intelligence X search engine and data archive. |

|

Reconnaissance |

Assessed targets’ revenue potential and quickly exploitable vulnerabilities to prioritize organizations capable of making large extortion payments. |

|

Initial Access |

Sent email spam followed by phishing messages and calls on Microsoft Teams. |

|

Initial Access |

Directed victims to fake VPN login websites during phishing campaigns. |

|

Initial Access |

Deployed information-stealing malware like “Lumma” and “StealC.” |

|

Initial Access |

Brute-forced accounts for external remote services like RDP and virtual network computing (VNC). |

|

Initial Access |

Purchased pre-established access through initial access brokers (IAB). |

|

Malware |

“IcedID:” Loader malware used for command-and-control (C2) and delivering advanced malware like ransomware to compromised systems. |

|

Malware |

“Pikabot:” Loader malware with extensive defense evasion capabilities. |

|

Malware |

“QakBot:” Loader malware with information-stealing functionalities. |

|

Exfiltration |

“Rclone:” Command-line tool for syncing and transferring stolen files to remote storage. |

|

Exfiltration |

“WinSCP:” File transfer tool for securely extracting sensitive data from compromised systems. |

|

Exfiltration |

“FileZilla:” File transfer protocol (FTP) client for uploading stolen files to external servers. |

|

Exfiltration |

“cURL:” Versatile command-line tool for uploading stolen data to remote servers |

Behind the Scenes of Black Basta’s RaaS Operations

Black Basta operated with a sophisticated organizational structure, ironically resembling that of legitimate cybersecurity companies and likely drawing inspiration from the former “Conti” RaaS group. This structure allowed multiple members or teams to work simultaneously toward compromising a target organization. Black Basta maintained clearly defined roles and pay systems, ensuring streamlined and efficient operations. Key roles included:

-

Intrusion Specialists: Responsible for gaining initial access through phishing campaigns.

-

Managers: Oversaw planning and execution of campaigns.

-

Developers: Focused on maintaining and upgrading ransomware.

The leaked messages revealed over 20 unique users involved in Black Basta’s operations, including the group’s leader and other key operators. Some users were external to the RaaS group and collaborated on or developed other malware, such as “QakBot” and “DarkGate.” Black Basta often purchased access to these tools for its campaigns, maintaining active communication with their developers for troubleshooting and deployment guidance. This interaction sheds light on the collaborative nature of RaaS groups and how they leverage external expertise to scale their operations efficiently.

Key Members of Black Basta

|

Username |

Role |

|---|---|

|

“Trump”/“Tramp” (aka GG, AA) |

The group’s leader, identified as Oleg Nefedov, who was arrested in 2024 during a trip to Armenia but used high-level connections within the Russian state to secure his release. Nefedov oversaw all operations and held final authority on ransom payment demands. |

|

“Tinker” |

A senior member who managed call centers and specialized in phishing campaigns targeting external remote services like VPNs and RDP. Also worked as an affiliate for “BlackSuit” (aka Royal) ransomware, another spinoff of Conti. |

|

“Lapa” |

An administrator responsible for operational tasks, including attacks on Russian banks. Likely the user “zazum” on Russian-language cybercriminal forum Exploit, this individual sold botnet access on the dark web and embodied Black Basta’s approach of targeting high-profile organizations while maintaining strict selection criteria for affiliations. |

|

“Cortes” |

Creator and leader of QakBot, though not directly affiliated with Black Basta. Likely a Russian national who distanced themselves from the group’s attacks on Russian banks. Has collaborated with numerous RaaS groups, including “Revil,” Conti, and “Cactus.” |

|

“Usernameugway” |

Likely the user “RastaFarEye” on Exploit, known for selling DarkGate malware. Faced numerous complaints from forum users, leading to their account being banned. |

Reading Between the Lines: Forecasts from the Leaked Logs

Black Basta Tactics Will Remain a Persistent Threat

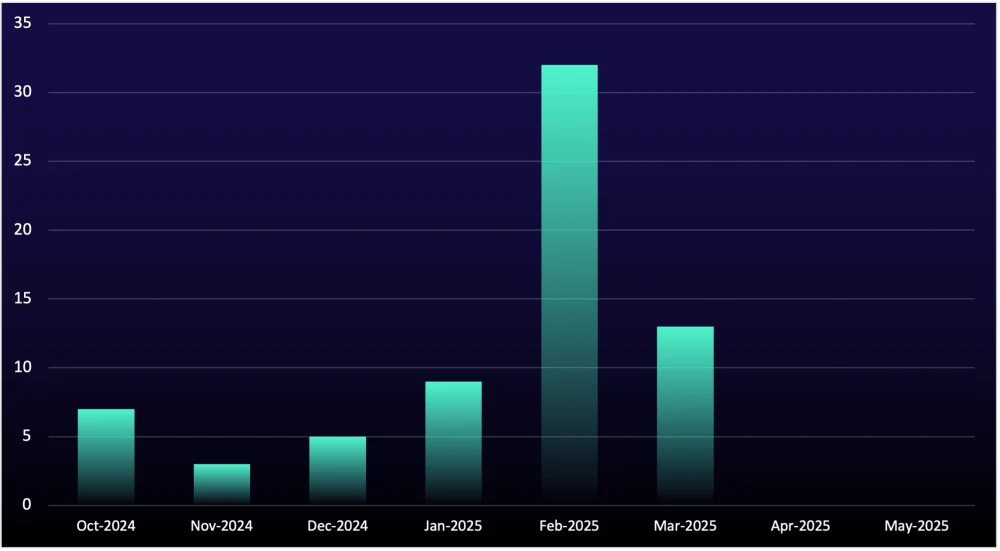

Figure 1: Volume of help-desk phishing events on Microsoft Teams targeting ReliaQuest customers in 2025

In May 2024, ReliaQuest uncovered Black Basta’s use of mass email spam, Microsoft Teams phishing, and fake help-desk impersonation to gain initial access. Despite the group’s collapse, these tactics persist. Since February 2025, Teams phishing attacks for initial access have held steady, with a significant spike in April 2025, accounting for over 35% of Black Basta-style phishing incidents targeting ReliaQuest customers.

The Black Basta name may have disappeared, but its former operators are likely still active, continuing to use their established tactics to target businesses. As such, organizations must remain vigilant against methods originally linked to Black Basta and adapt defenses accordingly.

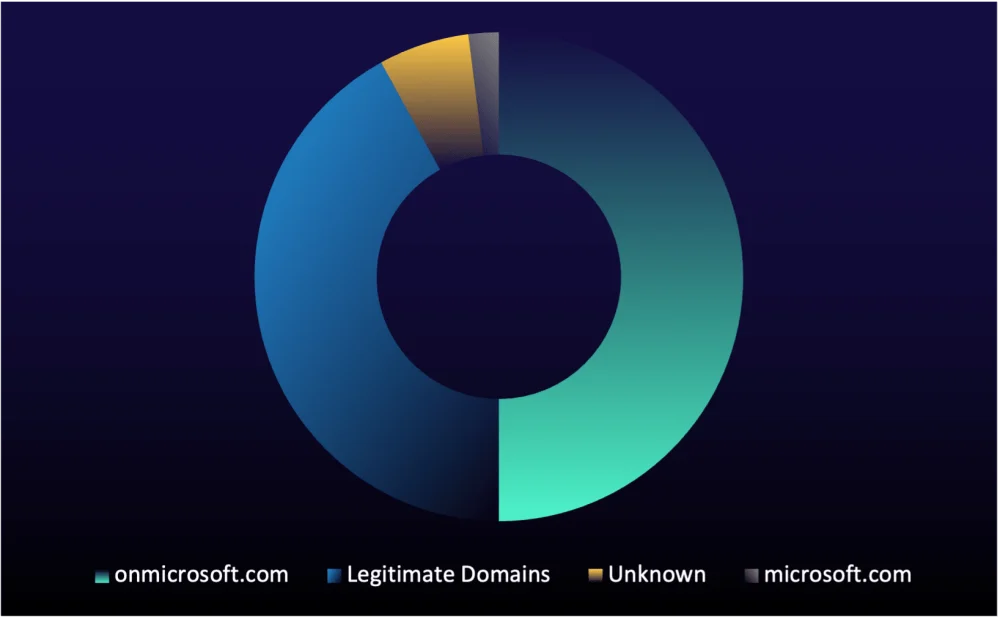

Figure 2: Sources of Microsoft Teams phishing

-

Between February and May 2025, half of the Teams phishing attacks we observed originated from onmicrosoft[.]com domains—a trend likely to continue due to the ease of creating and rotating these accounts.

-

Breached domains from legitimate organizations accounted for 42% of the observed attacks, enabling attackers to impersonate legitimate traffic and posing a significant threat. However, since these domains require the compromise of another organization first, making them harder to acquire, they will likely remain a secondary choice compared to onmicrosoft[.]com accounts.

-

microsoft[.]com accounts stand out as an even stealthier option than onmicrosoft[.]com. Commonly used for legitimate communications like Microsoft support and product notifications, these accounts are less likely to raise suspicion. However, due to their extreme difficulty to obtain and stricter defense measures, they will likely constitute only a small fraction of Teams phishing attacks.

While onmicrosoft[.]com domains are easier for attackers to obtain and currently dominate Teams phishing campaigns, microsoft[.]com domains—though harder to acquire—pose a far greater risk because they carry the legitimate Microsoft domain and add greater credibility to phishing campaigns.

Although onmicrosoft[.]com domains will highly likely remain the primary choice for attackers in the near future(within three months), efforts to gain access to microsoft[.]com domains are increasing. This shift could soon elevate the sophistication and danger of these phishing campaigns.

Case Study: In May 2025, ReliaQuest responded to two Teams phishing incidents targeting customers in the finance and insurance sector and the construction sector. In both cases, attackers deployed a flood of email spam followed by Teams phishing and vishing attempts. Using address like “administratorIT.onmicrosoft[.]com” and “supportbot[at]supportteamits.onmicrosoft[.]com,” they posed as a help-desk representative to contact and deceive users.

ReliaQuest’s detections promptly alerted the customers’ security teams, enabling a quick and effective response. Investigations confirmed that none of the targeted users granted the threat actors access to their machines; instead, users either ignored the Teams messages or became suspicious and hung up the calls. One organization had previously distributed a workflow to employees with clear steps to follow during email spam attacks. This incident underscores the value of user education and demonstrates how informed and empowered employees can serve as a critical first line of defense against phishing threats.

Cactus Likely the New Base for Black Basta Affiliates

The shutdown of Black Basta’s data-leak site, despite the continued use of its tactics, indicates that former affiliates have likely either migrated to another RaaS group or formed a new one—similar to their actions following the fall of Conti. The most probable scenario is that former members have joined the Cactus RaaS group, which is evidenced by Black Basta leader Trump referencing a $500–600K payment to Cactus in the leaked chats. This indicates a close working relationship between the two groups. Supporting this theory is a spike in organizations named on Cactus’s data-leak site in February 2025, coinciding with Black Basta’s site going dark. However, Cactus hasn’t named any organizations since March 2025, suggesting a realistic possibility that the group is either lying low to avoid attention or has disbanded altogether.

Figure 3: Organizations named by Cactus

Another plausible scenario is that former Black Basta members may join the RaaS group “Blacklock,” which recently rebranded from “Eldorado” and named over 50 organizations on its data-leak site in May 2025. The addition of “Black” to the name draws an interesting parallel to Black Basta, while the fact that Eldorado’s original members spoke Russian further strengthens this connection. An influx of Black Basta affiliates to Blacklock could position this group to scale its operations significantly, effectively picking up where Black Basta left off.

Evolving Attack Strategies Will Include Python-Based Payloads

In the leaked chat logs, Black Basta’s leader Trump referenced two dark-web profiles: “SebastianPereiro” and “marmalade_knight,” both members of Exploit forum. SebastianPereiro was linked to discussions about a Microsoft Teams zero-day, while marmalade_knight contributed to conversations on brute-forcing tool configurations. Trump likely shared these profiles to facilitate knowledge sharing and help other Black Basta members replicate similar tactics. However, these references provided a trail that we investigated further.

We identified two more Exploit accounts that interacted with both SebastianPereiro and marmalade_knight, which have a high likelihood of being previous Black Basta members. For operational security, their usernames have been modified:

|

Alias |

Noteworthy TTPs |

|---|---|

|

Itworkers |

Username mimics help-desk employees, aligning with Black Basta’s Teams phishing campaign. Sought access to partner.microsoft[.]com accounts and the source code for a remote-access trojan (RAT) from other forum members. Likely a former member of Black Basta’s initial access team. Recently launched a mass phishing campaign using attacker-in-the-middle (AiTM) session token capture for Google accounts. |

|

Codeseller |

Specializes in search engine optimization (SEO) poisoning to drive traffic to malicious sites. Recently sought someone to build an encryptor for their “Smoke Loader” malware. Likely a former member of Black Basta’s initial access team. |

The online activity of these two users, combined with insights from our investigation, highlight several potential tactics that former Black Basta affiliates may adopt:

-

Expanded Teams Phishing: Leveraging partner.microsoft[.]com accounts to impersonate legitimate Microsoft domains—a dangerous tactic already observed in attacks targeting ReliaQuest customers—effectively removes common indicators of malicious activity. This tactic increases the likelihood of successful Teams phishing attacks against end users.

-

Google/Gmail Account Phishing: UsingAiTM phishing techniques, attackers bypass multifactor authentication (MFA) by capturing session cookies, granting attackers unauthorized access. This access can lead to personal disruptions like through banking fraud or serve as a launchpad for attacks on organizations if employees use Google accounts within corporate networks.

-

SEO Poisoning: Attackers drive traffic to compromised websites using search engine keywords to deliver new encryptors via Smoke Loader. This method allows them to target specific roles within an organization. For example, terms like “court case” can target legal teams, while “printer troubleshooting” can be aimed at IT staff, infecting their machines through compromised webpages.

-

Python-Based Payload Delivery: Python scripts are used to deploy malicious files on compromised hosts after a phishing campaign. Paired with Teams phishing, this stealthy approach leverages tools like cURL to make the activity appear as legitimate administrative work, masking the payload delivery.

Case Study: In May 2025, ReliaQuest responded to a Teams phishing alert for a customer in the manufacturing sector. The phishing campaign originated from “ACTgroup620.onmicrosoft[.]com” and posed as “IT Support.” The attacker manipulated a user into joining two remote sessions via Quick Assist and AnyDesk, allowing them to quickly gain control of the user’s host. Once inside, the attacker began enumerating the network to identify domain assets and privileged accounts—a tactic commonly seen in Black Basta-style campaigns.

However, this attack introduced a unique twist: the use of Python to execute cURL and download a malicious .md (markdown) file from the IP address 161.35.60[.]146. The file was then executed as a Python script to establish C2 communications.

ReliaQuest detected the activity and worked swiftly to isolate the compromised host from the network, effectively halting the attack and providing the customer’s security team with critical time to perform further remediation. The use of Python scripts in this attack highlights an evolving tactic that’s likely to become more prevalent in future Teams phishing campaigns in the immediate future.

Step Up Your Defenses

ReliaQuest’s Approach

Threat Intelligence: ReliaQuest’s Threat Research team continuously tracks emerging threat actors and evolving TTPs, like the progression of Teams phishing attacks, to stay ahead of threats. We quickly feed the latest indicators of compromise (IOCs) into GreyMatter to ensure our customers are protected against ever-changing exploitation methods.

Threat Hunting: ReliaQuest actively hunts for threats such as Teams phishing, the use of unauthorized remote-access tools, and unusual C2 network traffic. By analyzing behavioral patterns and using advanced detection techniques, organizations can identify and mitigate risks before they escalate into security breaches.

Detection Rules: Customers should implement detection rules, which are tailored to detect malicious script execution, unauthorized access attempts, and other anomalous activities. Combined with GreyMatter’s agentic AI to enhance analysis and investigation, these measures significantly reduce the chances of a successful attack.

GreyMatter Automated Response Playbooks: For the fastest containment and response, implement Automated Response Playbooks like “Terminate Active Session,” “Reset Password,” and “Isolate Host” to prevent attackers from accessing key systems and deploying ransomware. For extra protection, consider configuring these Playbooks to “RQ Approved” to allow ReliaQuest to handle threat containment on your behalf.

Your Action Plan

Follow these steps to protect your organization from Black Basta affiliate campaigns:

-

Educate Employees: Our customer stories consistently show that informed users are the strongest defense against email spam and Teams phishing. In the incident detailed in this report, end users recognized the attacker’s objectives and responded appropriately when their mailboxes were flooded with spam. This awareness helped them identify malicious activity and prevented attackers from using social engineering to gain control of their machines through remote sessions.

-

Prevent Google Account Use on Company Devices: To defend against mass phishing campaign by Black Basta affiliates, implement a clear policy prohibiting personal Google accounts on company devices. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) should explicitly ban this practice, and browsers like Google Chrome should be globally configured to block logins with personal Google accounts.

-

Monitor for Unauthorized Python Activity: Attackers are increasingly using Python after successful Teams phishing attacks. Regularly audit for unauthorized Python script execution, particularly scripts that download or convert .md files, as this behavior may signal attempts to establish C2 communications.

IOCs

|

Artifact |

Details |

|---|---|

|

administratorIT.onmicrosoft[.]com supportbot[at]supportteamits.onmicrosoft[.]com ACTgroup620.onmicrosoft[.]com |

Sources of Teams phishing |

|

161.35.60[.]146 |

C2 IP Address |

[ad_2]

Source link