[ad_1]

Ever messaged a support bot on your fintech app and thought, “Is this even a real person?” I surely have.

Now imagine that person you’re talking to is locked inside a guarded building, working 14-hour shifts under threat of violence. Sounds a bit far-fetched, but that’s the reality for tens of thousands trapped in Cambodia’s scam compounds.

More than 100,000 people are believed to be caught up in this. They’re not just scamming for fun, but almost all of them are being forced to. These “modern-day slaves” are pretending to be customer service reps, building fake e-wallet platforms, and sweet-talking victims into sending money.

However, rather than enjoying doing it like your everyday work, if one of them misses a target, they’re going to expect a beating.

This is part of a USD $40 billion digital fraud economy stretching across Southeast Asia. And it doesn’t run on the dark web. It runs on familiar fintech tools, which mostly are APIs, KYC checks, and fake dashboards.

Same tech, but different intent.

How Cambodia’s Scam Compounds Took Root

Back in 2020, when borders shut and online gambling dried up, scam networks in Cambodia adapted fast.

Empty hotels and casinos were transformed into fraud factories. All they needed were victims, so they lured them in with fake job ads offering data entry work, IT support, or marketing roles.

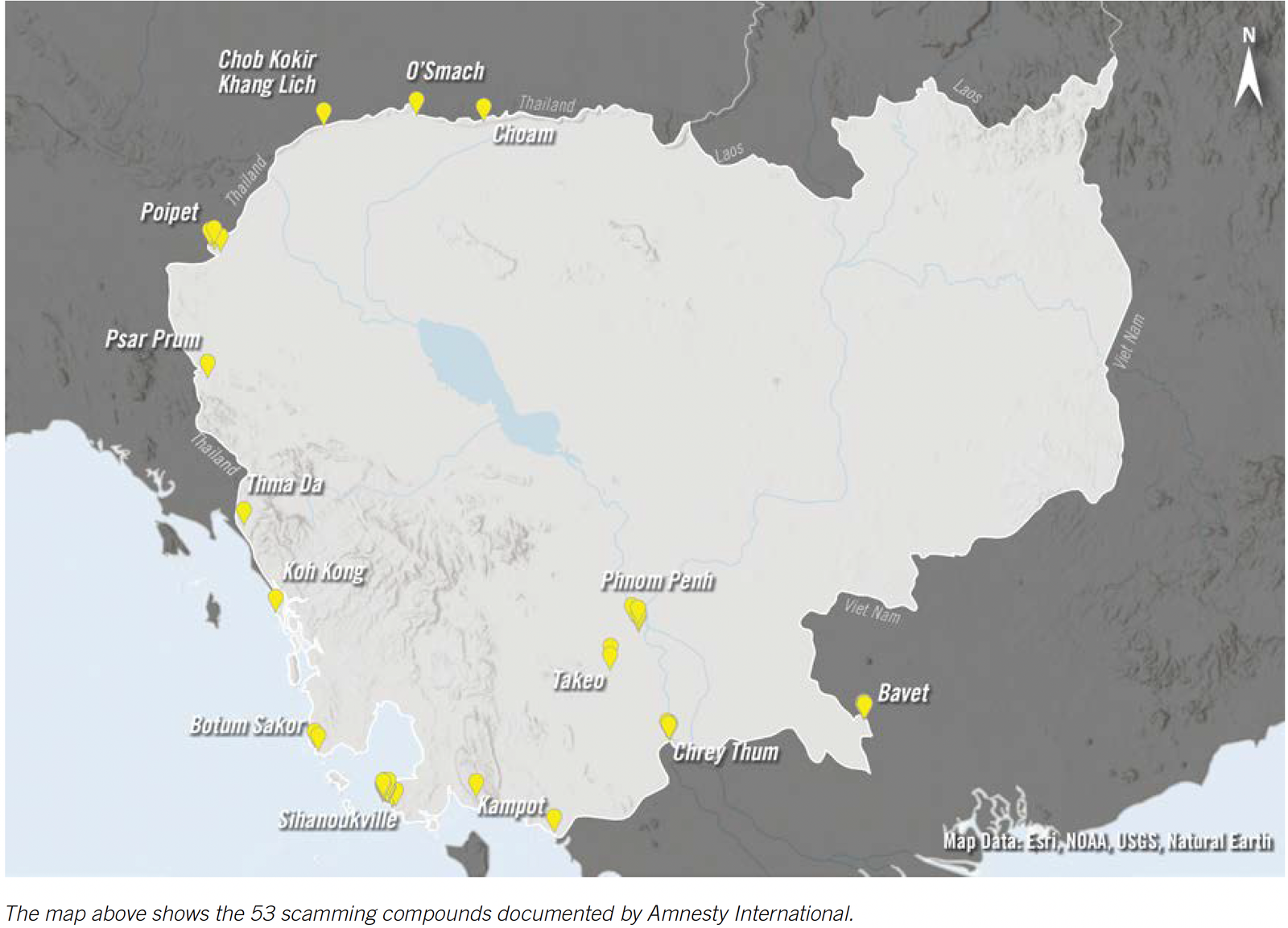

Amnesty International recently identified 53 active scam compounds, with at least 45 more suspected sites scattered across the country. Many of these compounds have been operating in full public view for years. The media was already reporting on them in 2022.

Still, most have never been shut down.

Survivors describe high walls, barbed wire, cameras, and guards. Torture rooms were common. One survivor said they were beaten, electrocuted, and starved for not meeting daily quotas. Another said they were forced to watch others being tortured as a warning.

Rather than some disorganised crimes, these operations have a clear structure with departments for different scams, floor managers, translators, and even training sessions. One compound staged fake professional photo shoots to mass-produce fake Thai IDs for banking fraud.

The report noted that some victims were resold from one compound to another, five, six, or even seven times. With each sale, conditions only got worse. Many described being treated like property, with their value negotiated over messaging apps.

The July Raids Didn’t Change Much

In July 2025, Cambodian police raided compounds across five provinces, arresting more than 1,000 people and seizing digital evidence. It looked decisive on the surface. But Amnesty’s findings suggest the impact was limited.

In at least 20 of those compounds, abuse continued even after police “interventions.” In many cases, officers didn’t even enter the buildings. They waited outside while compound handlers brought victims out. It looked more like a staged exchange, with victims quietly passed off while authorities stood by.

Phnom Penh’s infamous site, raided back in 2024, was a textbook example. Over a thousand foreign nationals were detained. But when Amnesty followed up, survivors like Lisa, a Thai teenager who managed to flee one time, were captured and were still being tortured months later.

Many so-called rescued victims weren’t treated as such. They were sent straight to immigration detention, sometimes held for weeks or months, without medical attention or legal help. In most cases, they were never officially recognised as trafficking survivors.

Scam Compounds Operate Like Startups, But with Slaves

I would go as far as to say that the scam compounds in Cambodia aren’t even trying to hide. From my readings and understandings, they are running openly in broad daylight, like tech startups, but just with human rights abuses baked into their workflow.

Survivors and investigators have described that there is some sort of an organised structure within the compounds, where victims are grouped into teams with designated managers, quotas, and performance metrics.

There are KPIs, dashboards, and even team leads. One group handles dating scams, another investment pitches, and another customer support. Workers are rotated, scored, and threatened. The more money you bring in, the better your food or treatment.

Slack off? You’re punished, often violently.

The tools used are also sophisticated, not like your typical village-type scamming operators. Employees are forced to use scripted chat flows, automated translation tools, and VPNs to mask IP addresses.

One survivor even said that they could view their “performance” in real time, just like sales reps in a real firm. But their freedom depended on hitting numbers.

Resale is also quite common. Some victims were sold between compounds like property, especially if they failed to meet scam quotas. In one case, a survivor reported being transferred seven times across different sites, each move bringing worse conditions and greater violence.

A modern type of slavery, if you will.

Everyone Knows. So Why Is It Still Happening?

It’s not that the problem isn’t obvious. What’s harder to understand is how it’s been allowed to carry on for so long without real consequences.

Despite Amnesty’s research, out of the 53 known scam sites, only two were actually shut down. Many are still fully operational. In fact, some of them had already been “raided” before and yet are “allowed” to continue to run with minimal disruption.

Prosecutions? Rare. Authorities claim to have launched investigations, but very few ringleaders have faced justice. Most perpetrators remain untouched.

Meanwhile, victims continue to be criminalised. Instead of receiving protection, many are detained for immigration offences or deported quietly. There’s little in the way of compensation, rehabilitation, or even acknowledgement that they were trafficked.

In 2024, the US sanctioned tycoon Ly Yong Phat, a powerful figure with deep links to Cambodia’s ruling party, for allegedly profiting from cyber scams and forced labour. But on the ground, very little changed.

And when journalists try to dig deeper, they’re silenced. In 2023, Cambodia shut down Voice of Democracy, one of the last independent outlets reporting on the scam economy.

So the scam compounds remain. Walled in. Staffed by the abused. Running on stolen tech and stolen lives.

Featured image: Edited by Fintech News Philippines based on images by Sorapop and www.slon.pics via Freepik.

[ad_2]

Source link

Click Here For The Original Source.