[ad_1]

Introduction

Cyber-enabled fraud, or “cyber scams,” have emerged as an increasingly urgent security concern in the last two years. The compounds out of which they operate exist in multiple locations globally but have been most prolific in the special economic zones (SEZs) and fragile spaces in the Indo-Pacific region, especially Southeast Asia, where they have rapidly altered the transnational organized crime landscape. Technological developments, combined with rapid digitalization, weak governance, limited law enforcement capability in the areas where scam centers are most concentrated, and lax regulation of key markets like cryptocurrency have created a perfect storm for criminal enterprises to rapidly and efficiently scale-up their operations. This is leading to significant financial losses worldwide, often with a heavy emotional toll for scam victims. Scam centers rely on forced labor, trafficking in persons, or lack of economic opportunity to ‘staff’ their operations, in which many people work in support or peripheral roles unrelated to direct scamming activity. Cyber-enabled fraud and scams challenge the rule of law and human rights in their host countries, while causing ripple effects and economic burdens for primary victim economies and increasingly threatening national, regional, and global security. In 2023, the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) labelled it as a “global crisis representing a serious and imminent threat to public safety.”

What Are Some Common Types of Online Scams and Fraud?

An online scam occurs when someone is tricked into giving away personal information, financial details or money via the Internet. Email scams have been around since the start of the online era, but modern scams make greater use of messaging services, social media, false websites, and even personal information databases obtained illicitly through the dark web or data breaches. Criminal networks also use fake job advertisements or immigration offers to lure individuals into ‘working’ for the scam centers and compounds. The mainstream proliferation of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) allows criminal networks to scale up the scope, precision, and efficiency of their operations and is rapidly lowering the barriers to entry for new criminal networks to enter the scene. Recent findings from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reveal a 600% surge in AI-generated deepfake content linked to fraud in Southeast Asia in early 2024, underscoring the rapid adoption and increasing role of advanced technology in these crimes.

The most common type of online scam associated with the scam centers or compounds in Southeast Asia is the one commonly referred to as “pig-butchering”. This term refers to the practice of grooming targets, or “fattening them up” before extracting the maximum financial value from them, or “slaughtering”. These scams are mainly a form of investment fraud, whereby targets are persuaded to invest in seemingly lucrative opportunities. Sometimes there are also elements of a romance scam, where targets unknowingly enter an online romantic relationship or dynamic with a scammer. There are other variations too; impersonation scams similarly pursue a financial outcome but rather than pose as a love interest, the scammer impersonates a family member or an authority figure such as law enforcement or a government official. Some scammers use phishing or malware to access their victims’ information. Most operations are prolonged, and scammers try to retain the same victim for a long time in order to extract the maximum funds possible.

Source: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Anti-Scam Handbook, UNDP Global Centre for Technology, Innovation and Sustainable Development, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.undp.org/policy-centre/singapore/publications/anti-scam-handbook.

Why Are So Many Scam Centers Located in Southeast Asia?

The relatively recent rise of cyber fraud compounds can be traced to the disruption of Southeast Asia’s gambling sector and Chinese criminal networks around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. As research conducted by the US Institute for Peace (USIP) in 2024 outlines, these criminal organizations had invested billions in developing extensive casino and hotel complexes throughout Southeast Asia, anticipating significant tourism revenue and profits. When pandemic restrictions halted international travel and casino operations, these criminal enterprises strategically repurposed this infrastructure for cyber-enabled fraud operations to maintain their income. This adaptation wasn’t driven by the physical infrastructure itself but by a calculated market response. Additionally, COVID-19 travel restrictions in 2020 resulted in the departure of many Chinese expatriates, further straining traditional revenue streams. Consequently, these scam centers have rapidly evolved into extensive complexes with a growing global reach, with victims of more than 40 nationalities trafficked into these compounds, highlighting the international scope of this crime. This expansion is not limited to Southeast Asia, as these operations are increasingly extending into regions like Africa and Latin America, indicating a growing global footprint.

Who Is Being Harmed?

Scams harm both the individual forced to work in the scam centers and compounds as well as the individuals and communities on the receiving end of scams. The number of affected individuals grows constantly, but it has been difficult to measure and quantify the impact as affected countries track fraud through reporting centers and metrics that vary from country to country, or that do not yet distinguish cyber-enabled fraud from other forms of fraud or cybercrime. A lot of cyber-enabled fraud and scamming goes unreported because victims feel shame or embarrassment, or do not have clarity on who to report it to. Yet growing interest in the issue is driving reporting and tracking. In 2024, cybercriminals earned an estimated USD 1.03 trillion from online scam operations. Between 2020 and 2024, an analysis of fraudulent cryptocurrency wallets estimated about $75 billion as the revenue from ‘pig butchering’ alone. In 2024, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center report showed losses from cryptocurrency-enabled investment fraud totaled over $6.5 billion. Key U.S. allies, partners, and markets have likewise been affected at similar levels and have accounted for this emerging, multifaceted threat in their annual national strategies for cybersecurity.

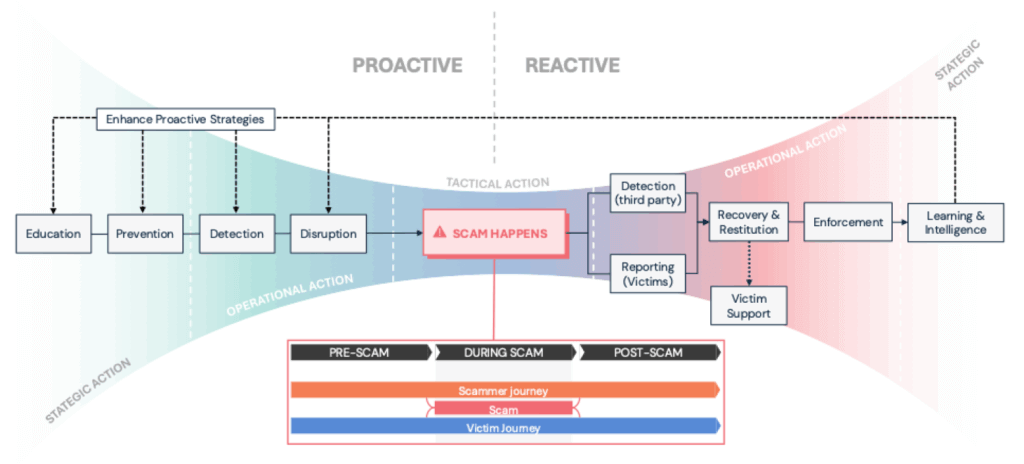

Mapping the Response

Online scams are a complex, fast-moving and multifaceted problem. National governments and other actors were initially slow to respond, but efforts are starting to gain traction. One of the primary challenges for countering online scams is that there is no single agency, community, or sector that can address this problem alone. Not only is it transboundary but it also sits at the intersection of other transboundary threats: organized crime, money laundering, human trafficking, and corruption. While there are legal frameworks addressing many of these issues, the way in which they intersect and unevenly apply to online scams makes it challenging to pursue and bring down scam operators. There are confusing and inconsistent terminologies being used (“internet fraud” “online scams” “cyber scams”) and associated concerns over the role and responsibility of private sector actors such as social media platforms, satellite internet providers, banking and financial services, and telecommunications providers. The law enforcement communities who track more traditional forms of transnational crime do not always have the capacity, training or tools to investigate and respond effectively. It is not a typical ‘cybercrime’ akin to ransomware, for example, nor is it fraud in the traditional sense because of its digital/cyber-enabled dimension. Reporting rates are uneven and not centralized, and conceptualizations of who is a victim vary and have been politicized.

These unique and overlapping challenges therefore require coordinated response: globally, regionally, nationally and with a wider ecosystem of actors such as banks, cryptocurrency companies, social media corporations, civil society actors, and law enforcement agencies.

To effectively combat this evolving threat, a multi-faceted and globally coordinated approach is essential, encompassing actions like easy national-scale online reporting, the establishment of a global fraud data-sharing hub, and measures to hold service providers responsible and liable. Such recommendations, as put forth by the Global Anti-Scam Alliance, demonstrate the variety of strategies needed to ‘turn the tide’ on scams and mitigate the devastating impact of cyber-enabled fraud on individuals, economies, and global security.

Source: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Anti-Scam Handbook, UNDP Global Centre for Technology, Innovation and Sustainable Development, accessed August 7, 2025, https://www.undp.org/policy-centre/singapore/publications/anti-scam-handbook.

This explainer presents an overview of national government responses to online scams from Australia, Canada, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (U.S). It considers if the country has established a specialized agency, center, or other body, including for reporting scams; relevant laws, strategies, and policies including relevant cybersecurity, cybercrime, and fraud policies; actions taken by relevant private sector actors such as telecommunications and banking; international coordination; and public awareness or education. These are not exhaustive studies of each country’s response but attempts to capture major lines of effort. Country profiles have been authored by Stimson Center staff and peer reviewed by external experts based in each country. The relevant and important efforts of civil society and international organizations are not studied in this explainer.

| Australia | Canada | Philippines | Singapore | Thailand | UK | U.S. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment of a specialized agency, body, or center for scams and/or online fraud | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Centralized reporting platform or agency | X | * | X | X | X | X | X |

| Specialized domestic legal or policy frameworks or strategies | X | ** | ** | ** | X | X | X |

| Efforts involving relevant sectors (telecommunications, banking) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| International coordination | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Awareness-raising/public education campaigns | X | X | X | X | X |

*An updated and streamlined system to be released in 2025.

**Focused laws or policies on cyber scams are embedded within existing laws or policies, such as on cybercrime or fraud prevention, rather than standalone.

Australia

Australia has adopted a multipronged response to prevent, disrupt, and mitigate cyber-enabled scams. Some argue that as a result of moving quickly and its multi-pronged approach, Australia has been successful in bringing down the rate of cyber-enabled scams. The primary national institution is the Australian National Anti-Scam Centre (NASC), established as part of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The NASC is tasked with three key areas of responsibilities: collaboration (technology and intelligence sharing), disruption, and awareness and protection with the end goal of intercepting contact between scammer and their targets. A hallmark of this multi-pronged approach is NASC’s creation of fusion cells and workgroups that bring together digital platforms, telcos, payment service providers, and crypto exchanges. NASC has also developed the Actionable Scam Intelligence Service, enabling “near real-time exchange of scam intelligence to organizations that can block and stop scams”. It has also scaled up website takedowns with over 10,000 websites, including investment, crypto, phishing, and online shopping scam sites.

NASC has worked closely with the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) and the Australian Federal Police (AFP) to ensure coordination and avoid duplication in reporting and response. The AFP-led Joint Policing Cybercrime Coordination Centre (JPC3) has been particularly effective in targeting payment redirection scams and money mules. In parallel, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) developed the Reducing Scam Calls and Scam SMS Industry Code (Scam Code), which blocked over 455.9 million scam calls and over 413.9 million scam SMS in 2024.

While the NASC focuses on prevention and disruption, Australian law enforcement works with ASEAN and other partners to trace and prosecute criminal actors. Legal frameworks such as the Cyber Resilience Framework (2023) and the Surveillance Legislation Amendment (Identify and Disrupt) Bill (2020) empower agencies to move quickly against transnational criminals and take down suspicious domains, cryptocurrency wallets, and websites while collecting evidence that can be used for prosecution. More recently, the Scam Prevention Framework (SPF) proposed under the Scam Prevention Bill (2024) united sectoral approaches under a common regulatory umbrella that addresses three sectors: telecommunications services, banking, and digital platforms including search engines, messaging, and social media. The framework imposes financial penalties for contraventions by regulated businesses and seeks to protect consumers and small businesses from telecoms and cyber scams.

In parallel, the Australian government has strengthened collaboration with telecommunications providers, mandating proactive filtering for scam text messages and blocking international inbound calls that spoof a domestic number. Fake financial ads are also blocked in Australia by requiring financial services advertisers to demonstrate that they are on a government-authorized list. Public awareness has also been prioritized through the national “Fighting Scams” campaign, which educates Australians on identifying, avoiding, and reporting scams across digital platforms. Additionally, in a major enforcement action, Australia recently revoked 95 company licenses for companies suspected of facilitating scam activity, particularly fraudulent investment schemes involving foreign exchange and digital assets. This deregistration comes as part of a broader crackdown on scam-related operations to protect consumers from financial fraud. The Australian Financial Crimes Exchange (AFCX) furthers this protection by providing security capabilities, technology, and intelligence in one central platform. AFCX also runs the Fraudulent Reporting Exchange (FRX) as a safe network that enables financial institutions to efficiently report and address fraudulent activities.

It is important to note that while the 2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy provides a broad framework for national cyber resilience, its primary focus is on threats like ransomware and data theft. However, several of its “cyber shields”, such as strong businesses and citizens, world-class threat sharing, and resilient regional leadership, do support scam prevention through public education, rapid threat disruption, and international cooperation, leading to an additional layer of scam prevention.

Internationally, Australia has invested in forming diplomatic and operational partnerships in the Indo-Pacific over time, leveraging them against transnational cybercrime. For example, the JPC3 partnership between the AFP and local policing subagencies focuses on “high-harm, high-volume” cybercrime. Regionally, Australia coordinates the Pacific Transnational Crime Network and the AFP’s largest international presence is in Southeast Asia, with 30 permanent members based in the region. Through these joint and interagency bodies, the Australian Police launched Operation Firestorm to target cyber scam centers in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe. As part of this, the Australian and Philippine police forces jointly shut down a scam compound in Manila in October 2024 in which they arrested 250 suspected scammers and collected digital and physical evidence to support arrests and rehabilitate victims in collaboration with international embassies. Additionally, the joint ASEAN-Australia Counter Trafficking Program (ASEAN-ACT) conducted detailed assessments on the state of play of forced criminality and human trafficking for cyber scams in Cambodia and outlined four sets of recommendations for a variety of government and non-government stakeholders.

Canada

The 2025 Canadian Cybersecurity Strategy recognizes, in its section on cybercrime, that Canadians report growing losses from cyber-enabled fraud. An estimated $227 million USD ($310 million CAD) was reported lost to investment fraud in 2024, nearly half of the total reported losses of $473 million USD ($644 million CAD). Spear phishing (targeted email scams) and romance scams were also among the top ten frauds reported in 2024. Scam victims and targets come from diverse demographic profiles, including along lines relating to language, ethnicity, or age.

There are two institutions empowered to address and respond to cyber-enabled scams and fraud. The Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC), established in 1993, collects information on fraud and identity theft. Its website includes extensive information about a wide range of fraud types that affect businesses and individuals alike, and in recent years has incorporated information on romance and crypto scams, which are prevalent in Canada. The CAFC is the central point for reporting cybercrime and fraud, allowing individuals to report incidents through their online system or by phone. It also publishes an annual report on fraud statistics and conducts diverse public awareness-raising and education campaigns. The CAFC is s jointly managed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Competition Bureau Canada, and the Ontario Provincial Police.

The CAFC works in tandem with the National Cybercrime Coordination Centre (NC3), established by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 2020. NC3 was a response to the rise of cybercrime in Canada and in line with priorities outlined in the Government of Canada’s (former) National Cyber Security Strategy, and the RCMP Cybercrime Strategy. The NC3 consists of police officers and civilians from various backgrounds and areas of expertise. The Centre works with Canadian law enforcement as well as national and international partners to help reduce the threat, impact, and victimization of cybercrime in Canada, including through building capacity. The CAFC and NC3 report to the same Director-General and are both stewarded by the RCMP as part of National Police Services.

In 2025, Canada will launch a new cybercrime and fraud reporting system to make reporting easier and more streamlined.

As in other countries, it can be challenging for Canadian victims to seek justice. This is largely because scam centers – and thus, the origin of the crime – are located overseas which creates jurisdictional barriers for investigation and evidence collection. One expert in Canada has additionally noted that losses must reach a certain financial threshold before law enforcement can take up a case. Staffing cybercrime police units adequately has been challenging for particular crime phenomena, and existing staff require training on the tactics and tools being employed in cybercrime, including scams. Canadian privacy laws are intended to protect individuals from harm but sometimes pose challenges for scam prevention or response measures because their emphasis on privacy and consent can complicate the collection and use of information needed for investigations.

Interviews with Canadian stakeholders and experts highlight the growing sophistication of scams, whether due to AI tools or phony websites that look increasingly credible. Victims are increasingly sending money through cryptocurrency transactions, but sometimes, bank-to-bank transactions are used. RCMP can trace fraud wallets and pattern the transactions in cooperation with international partners; based on fraud reports that tell RCMP what wallets victims used to send cryptocurrency to, and tracing of the transactions to that wallet. Project Altas, an initiative of the Ontario Provincial Police, is an example of this type of response. Yet the majority of funds lost to crypto scams go unrecovered often because the funds were routed through unscrupulous or foreign exchanges or were converted back into traditional currency to prevent the cryptocurrency exchange from accessing the funds.

The Canadian Telecommunications Association’s website outlines several measures it has in place to help prevent fraud. This includes Universal Network-Level Call Blocking (UNLCB), which blocks calls with blatantly false call display data. Calls with invalid numbers are automatically blocked, such as numbers like 000-000-0000 and others that don’t conform to international numbering plans. Caller ID Authentication (STIR/SHAKEN) protocols help protect Canadians from spoofed calls by verifying the authenticity of caller ID information. These protocols use digital certificates to confirm that a call is coming from the displayed number and has not been altered in transit. Telecom providers also use various spam filters to protect consumers from unwanted text messages and emails. Major Canadian banks also offer guidance and have implemented various safeguards against scams and fraud, in cooperation with major credit card companies, and have obligations to work with relevant government agencies and offices.

Regional Context: China/Myanmar

Unlike the country profiles, this section contextualizes the problem of scams within China-Myanmar relations. It is drawn from a commentary originally published by Sydney Tucker of the Stimson Center’s Myanmar Project in April 2025.

China’s approach to addressing online scams is shaped both by the rise of scam centers in neighboring Southeast Asian countries targeting Chinese citizens and by the impact these operations have on its relationship with Myanmar.

As a previous Stimson commentary, Cyber Scam Centers: A Growing Flashpoint in China-Myanmar Relations, lays out, scam centers are often located along the China-Myanmar and Thailand-Myanmar borders. They have increasingly become a concern for China due to the role of human trafficking and forced labor in the centers, and because of impacts on Chinese citizens as both trafficking and scam victims. This issue gained prominence in late 2023, coinciding with a broader deterioration in Myanmar’s internal stability and the rise of public pressure in China to address scams. China has shifted its stance toward Myanmar multiple times, initially backing the junta to prevent state collapse, but later distanced itself due to the junta’s failure to control border security and transnational crime, while still engaging diplomatically to preserve its strategic interests. China’s de-facto support of the October 2023 Operation 1027 offensive – an ongoing military operation led by the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BA) – was partly owing to the Alliance’s support for cracking down on scam centers. Their success in doing so forced many of the centers further south. While this has moved the problem away from China’s border, it has not stopped the trafficking of Chinese citizens.

Public outcry intensified after the abduction of Chinese actor Wang Xing in January 2025. His abduction and rescue raised question on the extent to which the Chinese government is involved in these operations. A grassroots movement titled “Stars Go Home Plan” began tracking Chinese victims of scam compounds and was quickly censored by the Chinese government.

China’s President Xi Jinping and Foreign Minister Wang Yi have been vocal about the threat posed to both Chinese citizens and the overall stability of a region by these scam centers. They have also praised the efforts of the Thai government and others in the region in shutting down scam operations. Rhetorical statements have been met with action, such as a joint Thai and Chinese coordination center as well as the largest repatriation of 200 cyber scam suspects back to China in February 2025.

Despite these efforts, scam operations continue to shift geographically, moving further from China’s immediate border and making their efforts to contain these operations far more difficult, especially in areas of Myanmar junta’s control. China has continued its efforts to use diplomatic clout and pressure to incentivize the prosecution and shutting down of cyber scam operations for the sake of the wellbeing of Chinese citizens as well as broader regional stability.

Philippines

Fraud and online scams have been an ongoing challenge in the Philippines for many years, but the issue was exacerbated significantly due to rapid digitalization during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the rise in online banking and the use of other online payment apps and services. In early 2024, the Philippine National Police (PNP) announced a more than 20% year-on-year increase for cybercrimes, particularly scams in online marketplaces, investment scams, and credit card fraud. A survey by the Global Anti Scam Alliance (GASA) indicated that two-thirds of individuals surveyed encounter scams at least once a month, and that scam losses reached approximately $8.1 billion USD in 2024 (about 2% of the Philippines’ GDP).

Cybersecurity and Cybercrime Frameworks

In February 2024, the government announced the National Cyber Security Plan 2023-2028 which broadly aims to proactively protect and secure cyberspace in the Philippines and includes a variety of actions and policy framework pathways to improve cyber security defense strategies. Scams are mentioned a few times, notably within the context of efforts to harden telecoms management including the threats of SMS scams, spam, and phishing. Two other related acts related to money mule accounts and blocking of online websites related to piracy have been proposed; one has passed (see AFASA section below), the other is still under discussion.

The Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (Republic Act 10175) established a legal foundation for addressing cybercrime. It identified a concrete definition and list for cybercrime acts, relevant penalties for such acts, and mandated the creation of specialized cybercrime units within the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) and the PNP, as well as an Office of Cybercrime within the Department of Justice (DOJ).

The Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Center (CICC) is the lead agency for implementing the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012. It is responsible for monitoring and preventing cybercrime; facilitating international cooperation, coordinating with government agencies, the private sector, and NGOs, and recommending legal updates. The CICC operates as an attached agency under the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) and collaborates with the National Privacy Commission (NPC), and National Telecommunications Commission. Under the Cybercrime Prevention Act, the CICC can request support from key agencies including Immigration, Drug Enforcement, Customs, National Prosecution, Anti-Money Laundering Council, Securities and Exchange Commission, and other relevant organizations. This structure acknowledges that cybercrimes frequently involve financial systems, cross-border activities, and established criminal networks.

The Senate is considering potential amendments to the Cybercrime Prevention Act to update it given the current situation in the Philippines with higher levels of internet users and devices,the increasing sophistication of criminal actors as well as the widespread emergence of online scams as the most prevalent type of cybercrime. Senate Bill 2570–proposed in February 2024– would grant the CICC greater mandate to coordinate on cybercrime prevention and investigation, ensuring the implementation of updated cybercrime laws, and integrate additional service providers into the prevention efforts. Additional laws under consideration are outlined here.

Private Sector Regulation

There are also specific regulations and laws passed to address fraud and scams within the financial sector. In 2022, the central bank of the Philippines, Bangko Sentral Ng Pilipinas (BSP), provided a circular memo requiring fraud management systems and consumer awareness efforts on the part of financial institutions it oversees. In July 2024, the government passed the Anti-Financial Account Scamming Act (Republic Act 12010, also known as AFASA) which aims to specifically outlaw and provide punishment for financial crimes including but not limited to operating money mule accounts, performing fraud or scams via social engineering, and other similar crimes. AFASA allows the BSP to investigate such crimes related to bank accounts, e-wallets, or other financial accounts and mandates additional responsibilities for financial institutions to implement a fraud management system.

Public Awareness and Reporting

Public awareness is a cornerstone of the Philippines’s strategy to combat online scams and broader cybercrime. The government has significantly expanded its cybersecurity education and reporting mechanisms.

In 2024, the DICT launched a cybersecurity awareness campaign as part of the National Cybersecurity Plan 2023-2028. The DICT regularly publishes updates on emerging scam tactics and cybersecurity tips, in combination with capacity-building initiatives. In the case where fraud does happen, the Philippines has numerous lines to report it. The primary official reporting channel runs through the Inter-Agency Response Center (I-ARC) via Hotline 1326, which is run by a consortium of DICT, CICC, NPC, and NTC with NBI and PNP support.

Singapore

International scamming of Singaporean citizens has been a major issue in recent years, with the number of reported crimes increasing nearly 50% annually most years since 2019. Singapore’s advanced digital infrastructure and relatively high digital connectivity rates make it a target for online scams. However, this has prompted a robust and complex response which includes significant regulatory and legislative efforts, law enforcement initiatives, and government engagement with telecommunications companies and banks, among other actors.

Legislative Response

There are different laws within Singapore that collectively provide a foundation for pursuing scammers and/or individuals that support them (i.e. money-mules). The 1993 Computer Misuse Act inhibits the use of computers or digital accounts for unauthorized or illegitimate access to programs or data. The Corruption, Drug Trafficking, and Other Serious Crimes Act of 1992 applies to money laundering. New sentencing guidelines updated both laws to cover offenses such as providing scammers with account credentials for use in scams as well as money.

The Penal Code 1871, particularly Section 420, is used to prosecute scam-related offenses involving cheating or deceiving someone in order to deliver property with value. This section includes terms of up to ten years and potential fines and was last amended in 2021. The 2019 Payment Services Act provides a framework for regulating payment systems and services in Singapore and has particular relevance to digital payments and financial tech companies which are often utilized to pass funds by scammers and scam victims. In 2024 the Monetary Authority of Singapore issued a circular with guidance on adoption of anti-scam measures by institutions that are licensed under the Payment Services Act and which are raising the cap for e-wallets.

In 2023, Singapore passed the Online Criminal Harms Act, which allows for directives to online service providers or other entities when there is suspected scam activity and mandates providers to establish systems or measures to counter such offenses or fix vulnerability points. Building on this Singapore’s government passed the Protection from Scams Bill in early January 2025, which allows the police to order banks to unilaterally halt banking transactions for individual accounts to prevent victims from transferring funds to scammers and to extend such restriction orders for up to six months. It entered into force on July 1, 2025. The Act recognizes that in many cases where there is significant financial loss, the victims willingly authorized the transfer of funds because of fraudulent actions of the scammers (such as through government impersonation, or romance and investment scams).

Aspects of the 2024 Law Enforcement and Other Matters (LEOM) Bill seeks to deter the misuse of local SIM cards for criminal activities, including scams by introducing penalties for errant subscribers, middlemen and retailers. According to the Ministry for Home Affairs, the number of local mobile lines involved in scams and other cybercrimes had quadrupled from 2021 to 2023 in an effort to get around measures introduced in 2022 to block overseas scam calls and text messages.

Anti-Scam Command and Law Enforcement

The creation of the Singapore Anti-Scam Command (ASC) in 2022 was a significant step forward to coordinate national efforts and has underpinned more recent legislative and implementation efforts. The center sits within the Singapore Police Force. Its work is predicated across six lines of effort: information management; intervention; deterrence; coordination with external stakeholders; public awareness raising; and international cooperation.

Given the nature of online scam strategies and operations, the ASC partners with more than 80 outside institutions to counter online scams. Importantly, key technical experts from other government agencies as well as staffers from key banks and other services are seconded to the ASC. This allows them to respond rapidly and in real-time to investigations, helping to trace funds and freeze bank accounts involved with scams and fraudulent fund transfers.

Banking Initiatives

In mid-2022, the Monetary Authority of Singapore along with the nonprofit industry group the Association of Banks in Singapore adopted a series of measures to help prevent losses, including a temporary self-service suspension of an account to prevent transfers (often called a “kill switch”), a locking feature to set aside certain funds which are not eligible for transfer, and instituting a default daily withdrawal limit for online withdrawals to avoid rapid draining of accounts. This was essentially required by banks operating in Singapore, although individual banks implement the “kill switch” differently. Another measure is the imposition of a 12-hour “cooling-off period” in which a transaction that is deemed “high risk” will not be available when an account is set up on a new device. Since 2022, there have been efforts to require facial verification for high-risk transactions using Singpass, a trusted digital ID program. Since 2023, the government has increased coordination with banks on additional preventative measures such as blocking account access from devices which give indications of malware infection.

Information and Telecommunications Initiatives

The Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) of Singapore leads engagement on digital economy and society in Singapore, and has been responsible for coordinating with telecommunications companies to limit scammer access. Since 2017, IMDA implemented progressive anti-spoofing measures: verification processes (2017), blocking spoofed numbers and malicious SMS links (2019), robocall pattern recognition (2020), blocking international calls with domestic numbers and SMS scanning (2022), and mandatory sender ID registration with “likely SCAM” tags (2023). Results show a 97% reduction in calls spoofing Singapore’s +65 country code through Q3 2023, with two-thirds of remaining calls identified and blocked as spam.

In support of these efforts, the Singaporean government worked with the private sector to develop Scamshield, an app which they advocate for citizens to install on their phones to block and filter robo- and overseas calls, track and blacklist bad actors, and/or double check if a link or message is a scam. The government also established a public awareness campaign, ACT Against Scams, which encourages users to “Add” security measures (like Scamshield or banking verification steps), “Check” for potential signs of scams, and “Tell” the authorities about any suspicious activity.

Thailand

Thailand faces a severe scam epidemic. According to a 2024 Global Anti Scam Alliance survey, nearly 90% of Thai citizens encounter scams monthly, with 60% reporting increased exposure compared to previous years. The financial impact is significant, with average losses of $1,100 per person in 2024—a $150 increase from 2023 and a substantial burden given Thailand’s GDP per capita of approximately $7,182.

In response the government has adopted a multi-faceted approach which combines legislation, institutional cooperation, technological measures, and cross-border enforcement to combat the growing threat of scams targeting its citizens.

Institutional Framework

The foundation for Thailand’s anti-scam infrastructure began in 2020 when the king passed a Royal Decree creating the Cyber Crime Investigation Bureau (CCIB) within the Royal Thai Police. This specialized unit is responsible for preventing and investigating technological crimes, establishing operational procedures, and supporting evidence analysis for cybercrimes. Additionally, the Royal Thai Police Royal maintains a Technology Crime Suppression Division within the Central Investigation Bureau, and the Department of Special Investigation has its Bureau of Technology and Cyber Crime.

In November 2023, multiple government agencies launched the Anti-Online Scam Operation Centre (AOC) as a centralized reporting mechanism. The AOC operates a national hotline (1441) for citizens to report scams and seek information. It coordinates across financial agencies to freeze and track funds following scam reports.

The Securities and Exchange Commission also established an Investment Scam Hotline in collaboration with the AOC and partnered with popular messaging platforms like Meta and LINE to block fraudulent activities. In January 2025, the Royal Thai Police created a “War Room” at headquarters integrating True Corporation (a major telecom provider) to analyze SMS and call patterns.

Legislative Response

In 2023, Thailand enacted the Emergency Decree on Technological Crime Prevention and Suppression to specifically address electronic and telecommunications fraud. Key provisions include:

- Requiring financial institutions and telecom operators to disclose transaction information when fraud is suspected

- Mandating responses to law enforcement information requests

- Enabling seven-day suspensions of potentially fraudulent transactions

- Criminalizing the provision of “mule accounts” with imprisonment and fines

A dedicated Commission will oversee implementation during the decree’s five-year term, after which the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society (MDES) and Royal Thai Police will evaluate its effectiveness.

In late 2024, the MDES proposed amendments to strengthen the decree by:

- Streamlining processes to refund victims when funds are frozen

- Increasing service provider responsibility when compliance failures contribute to losses

- Significantly increasing penalties for fraud involvement

These amendments received Cabinet approval in January 2025. In April 2025, the Thai Cabinet approved amendments to two existing emergency decrees to account for the growing threat of online fraud and cybercrime. The Emergency Decree on Measures for the Prevention and Suppression of Technological Crimes (No. 2) B.E. 2568 enhances online safety to address scams and digital fraud. The Emergency Decree on Digital Asset Businesses (No. 2) B.E. 2568 focuses on cryptocurrency markets to improve regulatory oversight of digital asset service providers.

Preventative Banking Practices

Following the 2023 Royal Decree, the Thai Bankers Association and Bank of Thailand launched the Central Fraud Register system in August 2024 to facilitate information sharing about suspected fraud. Beginning March 2025, the Bank of Thailand has expanded anti-mule account measures by adding risk levels, enhancing freeze measures, and requiring banks to block transfers to/from identified mule accounts, among other measures.

Telecommunications Enforcement

The National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) has implemented measures to limit access to “mule” SIM cards used by scammers.

One key effort was to do a review of all SIM card registrations, requiring people who registered between 6-100 SIM cards to update and verify identify information by mid-2024 or risk suspension and then termination of services. By mid-2024, the NBTC had suspended more than 3 million SIM cards. Other efforts to halt access are linked to identification and blocking of malicious or misleading links and websites for casinos, cryptocurrency investment, or other common avenues for scams.

Thailand also has a unique role given its geography, as Thailand has numerous cross-border lines in the border regions to provide internet, electricity, and in some cases fuel to neighboring communities. There are numerous online scam operation compounds located along the Thai-Myanmar or Thai-Lao borders, and many can access these resources either through legal or illegal connections. For example, the NBTC and Royal Thai Police cracked down on telecom towers at nearly 1,000 locations in 2024, disconnecting signals, adjusting antenna direction to limit services across the borders, and demolishing others. In February 2025, the government of Thailand announced broad cutoffs of electricity, fuel, and internet to key areas suspected of hosting scam compounds with only a day of official lead time before the bans go into effect. The threat was carried out but at least one scam operation remained operational, leaving the situation ongoing. Reports published in June 2025 indicate that authorities are considering extending such measures or targeting additional essential services.

United Kingdom

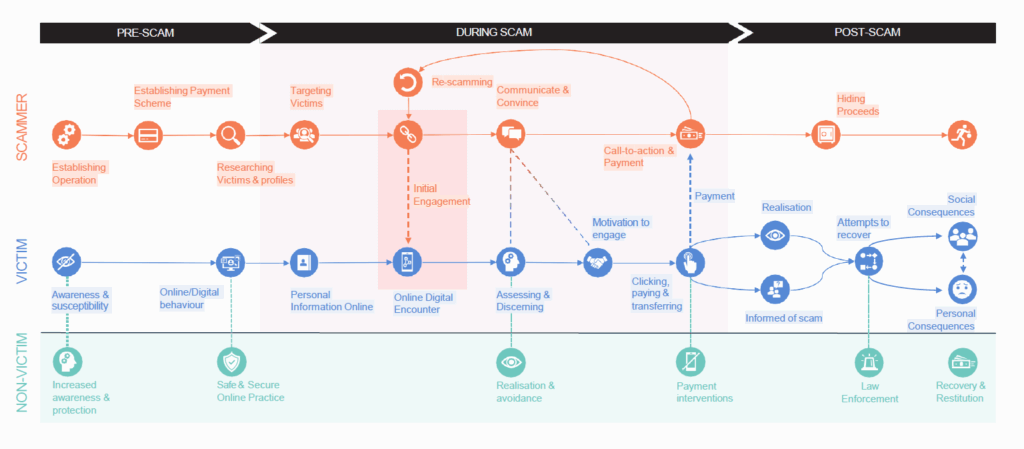

It is estimated that 76% of fraud cases in the United Kingdom (UK) now originate online, largely driven by lower-value scams like purchase fraud that accounts for 29% of total financial losses. The national response has focused on disrupting every stage of the “cyber fraud life cycle”. This includes proactive detection and takedown of digital threats, as well as close collaboration with financial institutions and technology companies to block fraudulent transactions and dismantle criminal networks.

The UK’s response strategy has emerged in recent years in tandem with the spike of cyber-enabled fraud. One 2021 study of British response to scams noted that responsibility for tackling the issue was unclear, creating a policy “leadership vacuum” and leaving financial institutions as the first line of defense in any instance of cyber fraud and in which UK law enforcement agencies were overburdened and under-resourced to meet the growing number of victims. Since then, the government has taken steps to centralize leadership and expand operational capacity.

In 2023, the UK passed the Online Safety Act (OSA) and announced a national Fraud Strategy aimed at reducing fraud by 10% by the end of 2024. The OSA introduced new legal duties for online platforms to assess and mitigate the risk of fraudulent content, including scam ads and impersonation attempts. Regulated services are now required to implement systems for detecting and removing fraudulent material, verifying advertisers, and cooperating with law enforcement. Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator, is responsible for enforcing these provisions and has begun issuing codes of practice to guide compliance.

The Fraud Strategy expanded the role of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), originally established in 2016 under the British National Cyber Strategy 2016-2021. The NCSC is the UK’s central incident response body for cyberattacks, playing a role in fraud prevention through intelligence sharing, technical disruption, and public reporting tools. The NCSC launched the “Share and Defend” hub, a national platform for threat intelligence sharing between government, law enforcement, and industry to proactively disrupt scam operations.

To strengthen investigative capacity, the government established the National Fraud Squad, a specialized unit tasked with targeting the most complex and high-value fraud operations. Action Fraud, the National Fraud and Cyber Crime Reporting Centre established in October 2009 now operated by the Home Office, has yet to see its promised replacement, despite the National Fraud Squad beginning operations. Action Fraud remains in use despite longstanding criticism for being outdated and ineffective. The government has committed to launching a new, state-of-the-art reporting platform, but delays have hindered progress, resulting in a critical gap in both victim support and reliable data collection.

The Joint Fraud Taskforce (JFT), originally established in 2017, was relaunched in 2021 with a renewed mandate to coordinate cross-sector efforts to combat fraud. Chaired by the Minister for Fraud and housed within the Home Office, the JFT brings together law enforcement, government, and private sector leaders to implement sector-specific fraud charters and drive collective action. It also monitors progress on national fraud reduction targets and facilitates data sharing across industries.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain. Some experts note that longstanding issues, such as fragmented leadership, limited digital forensics resourcing, and continued delays in replacing Action Fraud have undermined the effectiveness of national strategies. Only 14% of fraud cases are reported to Action Fraud or the police by victims, further demonstrating the public’s lack of confidence in the existing system and the broader tendency to not report which is also found in other countries.

To expand public engagement and prevention, the UK launched the National Campaign Against Fraud in February 2024. The campaign partnered with 30 key stakeholders like the National Crime Agency, the NCSC, and companies like X (formerly Twitter) and Google, and uses television and social media advertising to promote public awareness. The private sector has also taken on a more active role by creating the industry-led membership group Stop Scams UK representing the banking, telecommunications, and technology sectors. Stop Scams allows these sectors to collaborate rather than compete by overcoming regulator, data privacy, and legal obstacles. It also offers free public services to report and prevent fraud, including a phone service for consumers to verify potentially fraudulent calls or messages.

As part of its international efforts to combat cybercrime originating abroad, the UK hosted the inaugural Global Fraud Summit in March 2024, convening G7 and Five Eyes partners to develop a unified approach to tackling cyber fraud. The British Home Secretary and Security Minister, who oversee the JFT, led the summit in collaboration with G7 and Five Eyes partners. The parties endorsed a joint communique advancing a four-part framework to tackle cyber fraud, focusing on enhancing partnerships with the private sector. The framework includes a roadmap for building international partnerships and capabilities, empowering victims to overcome the stigma associated with fraud and recover lost assets with the help of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), tackle transnational organized crime actors, and disrupt the ability of scammers to target victims online.

United States

Scams and cyber fraud have skyrocketed in the United States in recent years, with reported losses quadrupling between 2020 and 2024. Fraud accounted for a majority of reported losses in 2024, which reached a record-setting $16.6 billion. The United States government employs a multi-faceted approach to counter cyber scams and fraud, combining regulatory frameworks, law enforcement efforts, and proactive prevention measures. While these are outlined below, currently no single agency is mandated to coordinate efforts to address cyber scam responses or support victims.

Several federal laws and agencies form the backbone of the U.S. regulatory response to cyber scams. Agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) regularly issue alerts and provide consumer advice on how to recognize and avoid various types of scams, including phishing, tech support scams, and fraudulent job postings.

The FTC is the primary agency for consumer protection in the United States, enforcing laws that prevent deceptive and unfair business practices. The Fraud and Scams Reduction Act of 2019 specifically tasks the FTC with raising awareness, identifying, and combating schemes to defraud consumers, including the creation of an Office for the Prevention of Fraud Targeting Seniors. The FTC actively disseminates educational materials and logs complaints through its website. And the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has sought to combat spoofed calls through adopting caller ID authentication (STIR/SHAKEN) in 2021 to identify legitimate calls and mitigate malicious robocalls.

The Department of Justice, particularly through its Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS), is responsible for investigating and prosecuting a range of cybercrimes including scams. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) is a foundational federal law used to prosecute unauthorized computer access, data theft, and other cyber offenses. The FBI, as the lead federal agency investigating cyberattacks, operates cyber squads in its field offices and works with international counterparts. The FBI manages the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), which collects reports of internet crime from the public, publishes annual reports highlighting the state of cyber-crime in the United States, and helps in freezing funds for victims.

In addition to these domestic efforts, the U.S. also works with a wide range of actors internationally to address cyber-scams and fraud. The Department of State’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (EAP) and the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), as well as USAID, have in recent years prioritized countering cyber scams originating in Southeast Asia through forming working groups and sharing information about cyber-scams collected from embassies and consulates with other agencies. The U.S. Department of the Treasury has applied Global Magnitsky sanctions three times against individuals enabling or running large-scale cyber scam operations. In 2018, the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone located in Bokeo Province and its owner Zhao Wei were sanctioned. In 2024 Ly Yong Phat, a Cambodian tycoon with ownership of properties and scam compounds where cyber scams emanate, was sanctioned, and in 2025 warlord Saw Chit Thu, his two sons, and the Karen National Army which he oversees were sanctioned for facilitating cyber scams.

The Trump Administration reportedly has placed countering cyber scams at the top of its Southeast Asia policy priorities, but a comprehensive approach has yet to coalesce. It is unclear whether a Biden Administration inter-agency working group on cybercrime led by the National Security Council’s Office of Cyber Policy will continue, and reductions of personnel and resources at many federal agencies which previously funded investigative and enforcement efforts against cyber scams will likely hamper efforts.

Given the rapid proliferation of cyber scams and fraud and the technical nature of the crime, it can be difficult for many victims to recover losses or seek justice. Local law enforcement agencies often lack resources to aid victims of cyber scams and have in some cases told victims that they do not have the capacity nor jurisdiction to process crypto-currency related scams or crimes. To assist scam victims, promote awareness, and provide guidance on countering the cyber-scam threat, non-government efforts such as Operation Shamrock and the Stop Scams Alliance have been established in recent years. But these organizations have limited resources and access to tackle the issue.

Many social media and messaging platforms such as Meta (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger) on which cyber criminals prey on victims are registered or headquartered in the United States. While most of these companies police cyber scam activity, critics argue that they do so in a shallow way despite pledges to increase monitoring and security measures to prevent cyber-enabled crimes. A May 2025 investigation by Wall Street Journal indicates that nearly half of all scam complaints tied to Zelle financial transactions were linked to Meta’s subsidiaries Facebook and Instagram. These organizations can likely do more to combat scams in the United States if sufficient public or government pressure is applied, as some have adopted additional safeguards in other countries such as the UK.

Conclusion

This explainer sought to outline the scope and nature of national responses to the rising challenge of online scams in seven countries which have been heavily targeted.

Every country studied has responded in ways that reflect their respective national contexts, political traditions, and existing capabilities. Responses also reflect the multi-faceted nature of the online scams issue, which straddles cybersecurity and cybercrime, fraud, and human rights concerns. Several of the countries surveyed are moving in the direction of establishing focused agencies or other bodies specific to online scams and frauds, often situated within broader anti-fraud efforts. Some are creating specialized policies or laws that tackle discreet aspects of the issue (such as acting as mules for money or SIM cards) or updating existing cybercrime/computer safety laws or anti-fraud strategies. Many have also introduced centralized reporting platforms or agencies, although the extent to which those well-utilized by scam victims varies. Awareness-raising efforts exist but appear to be somewhat limited in their impact and reach.

It is increasingly clear that national governments cannot act alone and must engage with relevant private sector entities such as banks, social media platforms, and telecommunications providers. Each of these entities has a different role to play in scam prevention, whether in flagging/pausing problematic transfers, removing and improving vigilance against false content, or putting in place technological blocks and fixes. Globally, it is evident that more coordination would be beneficial whether that is in the area of streamlining national law and policy; improving transborder evidence-sharing and law enforcement; or building cohesion in how private sector entities are engaged, notably social media platforms.

Stimson’s research process further identified that greater clarity around the role of different actors at local, national and global levels is needed to enhance cooperation and improve relevant law enforcement. More than anything else, political will to stop scams is a key determinant for success.

Future Stimson Center work on this topic will consider how international legal frameworks in the area of cybercrime, anti-trafficking, and anti-money laundering can be better applied and expanded to counter online scams.

[ad_2]

Source link

Click Here For The Original Source.