[ad_1]

One Sunday in Kanigarh, a remote Uttar Pradesh village an hour from Delhi, Tej Pal was sitting at home with his wife when he received a video call from the police.

A group of officers in light brown uniforms and distinctive black flat caps stared out at the farmer and rickshaw driver from the small screen of his Samsung Galaxy smartphone. “Your underage son has been found drunk,” they informed him. “If you want him released, you’ll need to deposit money.”

“I’m a poor man, a farmer. I don’t have any money,” he replied. It was a sweltering May afternoon and his son, Vikas Kumar, 17, had gone out for a swim with friends. He wasn’t reachable by phone. Tej Pal and his wife assumed the worst.

The inspectors were demanding 17,000-18,000 rupees — about £150. For Tej Pal, this was more than an entire month’s income, but he went to the village and asked a friend to transfer 10,000 rupees to the UPI code he’d been sent — a real-time QR-facilitated, cashless payment method that is near-ubiquitous in India. It was the entire contents of his bank account.

“You can speak to your son,” the officer told him.

Then the call cut out.

“I tried to call back over and over again. I was really scared for my son, but the phone number was switched off,” Tej Pal said. “We panicked and called other people to help find him. Then, a little while later, my son just walked in the house.”

Tej Pal’s son had not been out drinking. Nor had he ever been to a police station. Within a few minutes, it became clear the whole thing had been an elaborate scam.

Tej Pal is among thousands of victims of cyberscams in India

PRADIP KUMAR FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

India is in the midst of a cyberscam epidemic, and Tej Pal is one of its thousands of victims. Last year, Indians lost a staggering 228 billion rupees (£1.97 billion) to cybercriminals alone — a 206 per cent rise from 2023, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs.

The crime wave has been made possible by the giant technological leap that the south Asian nation has made in the past decade.

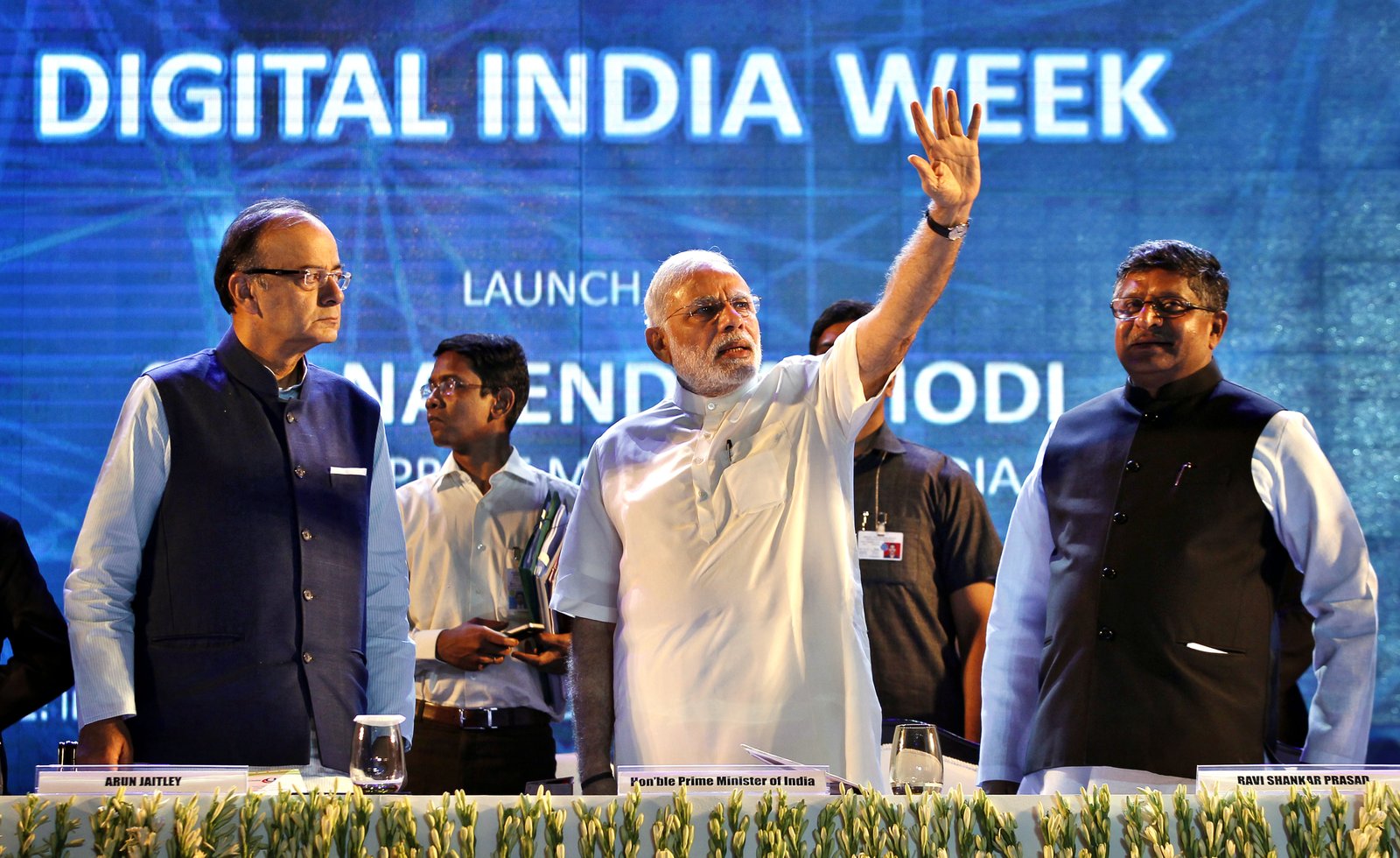

In 2015, the prime minister, Narendra Modi, launched his “digital India” initiative to provide e-government services to all citizens through digital infrastructure. A key part of this initiative is India Stack, which enables governments and businesses to build paperless services.

A cornerstone of India Stack is the unique biometric identity system, Aadhar, issued to more than 1.3 billion people. Services such as UPI are enabled by India Stack, and largely rely on the possession of an Aadhar number.

Today, mobile phones are in use across all parts of the country, from the bustling cities to the remotest villages, enabled by data packs which cost as little as 11 rupees per hour. Consumers and businesses in India engage in more digital transactions than any other country, and even the smallest — paying for a mango from a cart on a rural roadside, for instance — are now often done digitally.

Narendra Modi launching the digital India project in 2015

AJAY AGGARWAL/HINDUSTAN TIMES/GETTY

But in the shadow of this progress, an insidious parallel economy — cyberscamming — has proliferated due to lagging digital literacy and regulatory paralysis.

Tej Pal was duped by a rudimentary form of one of the most dangerous and harrowing forms of psychological extortion that has plagued Indians in recent years — the so-called “digital arrest” scam, a chilling co-opting of the government’s e-governance push. Citizens from all walks of life and socio-economic backgrounds have found themselves placed under so-called “digital arrest” by cybercriminals posing as police or government officials.

Victims are coerced into believing they are under criminal “e-investigation”, held “digitally hostage” — sometimes for months on end — and manipulated into handing over their savings.

Last month, a utility company employee committed suicide after digital arrest and harassment by a man posing as an officer from the Central Bureau of Investigation. He had lost 1.1 million rupees (£9,500).

In 2023, Indians lost 3.4 billion rupees (£29 million) to digital arrest scams. In 2024, this number shot up to 19.4 billion rupees (£168 million.)

• Police can’t stop cybercrime, so here are some real solutions

In March this year, an 86-year-old gynaecologist living in Mumbai was defrauded of 200 million rupees (£1.7 million) after being digitally arrested and held hostage in her home for more than two months. She was told she was under surveillance for money laundering. She received calls every three hours and was told not to leave her room. Her case would be handled under the “digital India” initiative, she was told — meaning she wouldn’t need to visit the police station. Instead, police would monitor her remotely.

Senior citizens, who are often not very digitally sophisticated, are more vulnerable, say cybercrime police, but the digitally literate are targets too. “Because so much personal data is either publicly accessible [in India], or leaked on the dark web the scammers are able to access your data and craft a personalised narrative,” said Sanjay Sahay, a prominent cybersecurity expert.

In June 2023, Ayush Agarwal, a 27-year-old software engineer was working from his room in Baloda Bazar, a town in Chhattisgarh state, central India, when he received a call from a FedEx employee. An automated voice in a crisp American accent, replete with standard muzak — a Richard Marx song — told him to press 9 to speak to customer care about a package.

A man’s voice on the other end recited Agarwal’s Aadhar number — his unique 12-digit identity code — then told him it had been used to ship a parcel from Mumbai to Taiwan. The man said the parcel contained illegal items, including 150 grams of the drug MDMA.

Agarwal was passed onto what he was told was the Mumbai cybercrime station, and told he could come in person for an investigation or opt for an “e-investigation” via Skype. He took the latter option. Over the course of three hours, the bogus officers sent him documents personalised with his name and Aadhar number. They made him give recorded testimony.

“They implied that I was in trouble, and they were going to help me,” he recalled. “They would insinuate that something terrible could happen to me. At other points they would reassure me.”

Richa Mishra, a journalist based in Delhi, was targeted on October 5 last year. Like Agarwal, she received a call supposedly from FedEx; like Agarwal, she was transferred to the “Mumbai police department”. She recalls that the background noise changed — to something chaotic like “the sound of a police control room.” Like Agarwal, she had been sceptical at first, but specific details only the police should have known changed her mind.

“They had my personal data” she recalls. “What scared me was they knew my office timings. They had my exact schedule.

“They planned to keep me in the trap for seven days. I was asked for all my personal details every two hours. An arrest warrant was issued in my name. I was imprisoned in my own house that day. It could have lasted for days. Even though I knew all about cyberfraud, I had been trapped.”

The digital arrest scam was invented by Chinese cybercrime syndicates operating from southeast Asia, mainly Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos, Indian police say.

Its success is due, at least in part, to confusion around the implementation of a new criminal code, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), enacted in India in 2023, which sought to modernise the legal framework by enhancing access to justice. Crucially, it incorporates provisions related to digital India — cybercrimes and digital offences.

• India rids penal code of last vestiges of the Raj

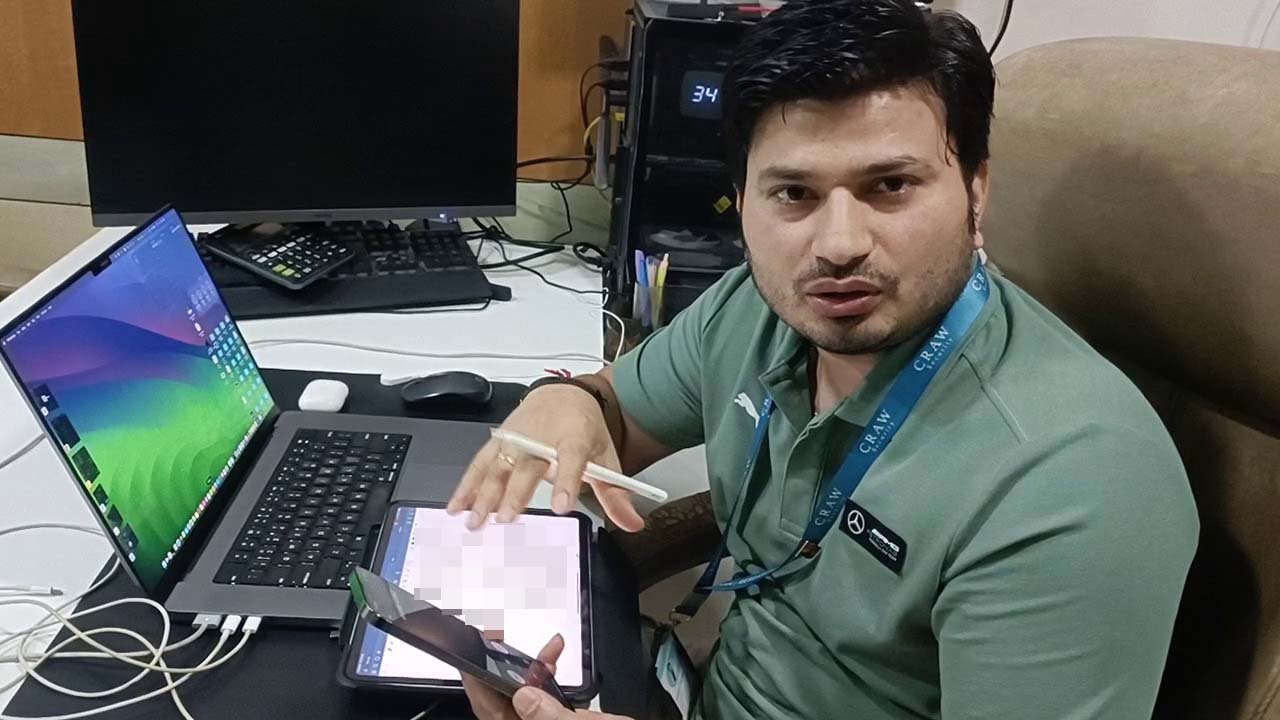

“People thought it was a new law, that BNS had digital arrest as a new methodology of arresting people. That’s why [BNS] was so important for scammers. It’s a kind of social engineering,” said Mohit Yadav, a cybersecurity expert who was himself on the receiving end of a digital arrest attempt. He photographed the scammer who appeared on his laptop screen dressed as a police officer.

The cybersecurity expert Mohit Yadav was himself targeted by a scammer pretending to be police

MOHIT YADAV

The experience of digital arrest continues to haunt Richa Mishra. “I can’t forget that day. I came out changed somehow. Even today this thing has left me with so much fear, things don’t feel normal. Now I feel scared when a phone call rings from an unknown number.

“The most difficult thing is to tell someone that digital arrest is not just a matter of being cheated of money. It’s mental harassment too. The most painful bit is when people around you belittle your experience.”

For Tej Pal, meanwhile, it has taken months of hard grind to recover his stolen savings. “I worked really, really hard to earn that money,” the farmer said. “I continue to be very ashamed of what happened. People told me I should go to the police, but what can the police do? There are so many big scams, what’s 10,000 rupees. Why would they bother?”

[ad_2]

Source link

Click Here For The Original Source.